Regulator blasts ExxonMobil’s Bass Strait maintenance, orders huge decommissioning push

Bass Strait partners ExxonMobil and BHP must plug 180 wells, dismantle ten platforms and tackle life-threatening corrosion after intervention by offshore safety regulator NOPSEMA.

Offshore safety regulator NOPSEMA has ordered ExxonMobil to plug 180 wells and start dismantling ten platforms from its vast Bass Strait operation.

The operator of the facilities off the coast of Gippsland, Victoria, must also fix dangerous corrosion on two platforms caused by a lack of maintenance.

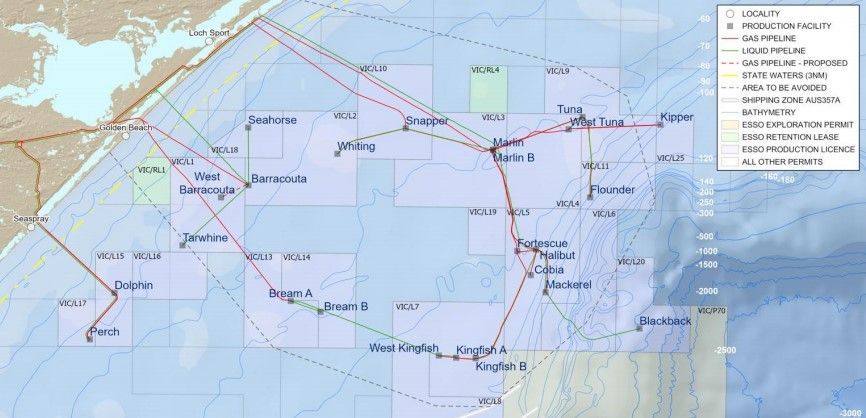

Exxon and its 50 per cent partner BHP have produced oil and gas from the Bass Strait since 1969 and now, after 42 years, must begin a gigantic clean-up.

Over four decades, Exxon drilled 421 wells, installed 19 platforms and laid about 600km of pipeline on the seabed.

Ten platforms, six pipelines and more than half the wells are no longer used for production. Another six platforms will cease production by 2025.

NOPSEMA's direction lists 180 wells that must be permanently sealed, or plugged, by September 2027.

Exxon must start dismantling the topsides of ten platforms "as soon as reasonably practicable" but no later than the deadline for plugging the wells.

The regulator said the deterioration of facilities as decommissioning is delayed puts at risk Exxon's ability to do the job without increased safety and environmental risks.

NOPSEMA considered Exxon's planning and proposed timing "not commensurate with the scale of decommissioning activities required."

The usually hands-off regulator has demanded an independent review of Exxon's decommissioning plans to identify ways to complete the work sooner.

NOPSEMA's actions attempt to head off two incentives that drive the current standard response from the industry to decommissioning: constant delay.

The owners first benefit by pushing back expenditure, and then if the ageing asset falls into disrepair, they can argue it is too dangerous to decommission fully.

NOPSEMA is investigating legal action against Woodside for a lack of maintenance of an 83m-long riser turret mooring at Enfield, which meant it can no longer be safely towed to shore for disposal.

The action against Exxon is the second time NOPSEMA has mandated dates for decommission to occur.

In February Woodside was told to complete the decommissioning of its Enfield oil field off the WA coast by 2025.

The regulator's blast at Exxon's performance is in stark contrast to the US-major's self-assessment.

"ExxonMobil Australia is committed to decommissioning our Bass Strait offshore facilities at the right time, and in the right way… ensuring they stay safe until we're ready to begin the decommissioning process," according to Exxon's website.

Exxon has recently spent more than $300 million "plugging and abandoning a number of wells in the Bass Strait that are no longer producing."

The cost of the work mandated by NOPSEMA will be many times that, giving a huge boost to offshore oil and gas employment just as increasing climate concerns cast doubts over future investment in new production.

Australia's offshore oil and gas producers are estimated to have a $52 billion clean-up bill over the next three decades.

Rusty and dangerous not acceptable

The offshore safety regulator also has concerns about the Bass Strait operation that are more immediate than decommissioning.

NOPSEMA today published three improvement notices requiring Exxon to fix dangerous corrosion on two platforms.

The steel supporting the West Tuna helideck has extensive corrosion that could cause a fatal failure under the weight of a helicopter. NOPSEMA concluded Exxon could have prevented the corrosion if it had painted areas of concern identified in 2016.

The West Tuna platform also had steel supporting a walkway "completely corroded away" that could result in the failure of the walkaway "leading to serious injury or death." The corrosion was found in November 2019, and Exxon did not plan to address it until a planned shutdown later this year.

In March, NOPSEMA inspectors on the Tuna platform found a section of walkway grating "only supported by a single severely corroded load bar, which if it failed, could result in personnel falling directly to the sea." Exxon identified the problem in 2016. The company now has 30 days to fix it.

The corrosion on the two platforms led NOPSEMA to conclude that Exxon's maintenance regime could not demonstrate its offshore facilities were "safe and without risk to health."

Exxon must now has 30 days to conduct a "fitness for service integrity assessment" of its nine operating platforms and implement at least temporary fixes to all problems identified.

NOPSEMA actions against Exxon are extraordinarily strong from a regulator often derided by unions as a toothless tiger.

It has found what was once the world's largest company that marketed its petrol a being a "tiger in your tank" to be severely wanting.

As climate pressures build on the oil and gas industry and concerns mount about ageing facilities, it seems the US producer has lost some stripes, and the local regulator gained some.

A hard sell for Australian offshore assets

The NOPSEMA decommissioning direction notes that BHP intends to sell its interest and "although such a company sale may not alter the title register, it is important for transparency that all parties understand the obligations" under law.

The note is a reference to Woodside's sale in 2015 of a subsidiary that owned the Northern Endeavour oil vessel.

The transaction then did not require regulatory approval because the companies listed on the title were unchanged. The new owner later went into liquidation, leaving the Federal Government with a clean-up bill of many hundreds of millions of dollars.

Under changes announced by Resources Minister Keith Pitt in December, a sale similar to Woodside's 2015 effort now needs approval and almost certainly would be rejected due to the inexperience and financial weakness of the proposed buyer.

Additionally, trailing liabilities will hold future sellers, not the Australian taxpayer, liable for decommissioning costs if a new owner fails.

BHP can still sell its stake in the Bass Strait, but the intersection of the pool of experienced and financially strong buyers acceptable to the Federal Government and companies with an appetite for ageing assets with declining production will be extremely limited.

In 2020 Exxon called off its planned exit from the Bass Strait after Pitt wrote to Exxon chief executive Daren Woods and forewarned him of the introduction of trailing liabilities.

ASX-listed Beach Energy had been reported as a likely buyer of Exxon's interest. Beach has very limited offshore experience and a market capitalisation of less than one per cent of Exxon's.

Main image: West Tuna platform, Bass Strait. Source: ExxonMobil Australia.