Westport bill may jump $1b to keep desalination plant working

Longer pipelines into Cockburn Sound must be built before port construction begins or 15 per cent of Perth's water supply will be lost.

Australian LNG producers are under pressure on emissions and decommissioning, and Santos wants to tackle both problems in one swoop at Bayu Undan, but it needs everyone to play along.

EXCLUSIVE ANALYSIS

Santos' plan to bury CO2 and delay decommissioning at its Bayu-Undan gas project is troubled by low returns and needs a myriad of deals with governments and partners to take off, according to recent internal company documentation seen by Boiling Cold.

Santos chief executive Kevin Gallagher and his team need a lot to go their way to realise this vital part of the company's net-zero by 2040 plan and not regret buying more of the ageing Bayu-Undan asset.

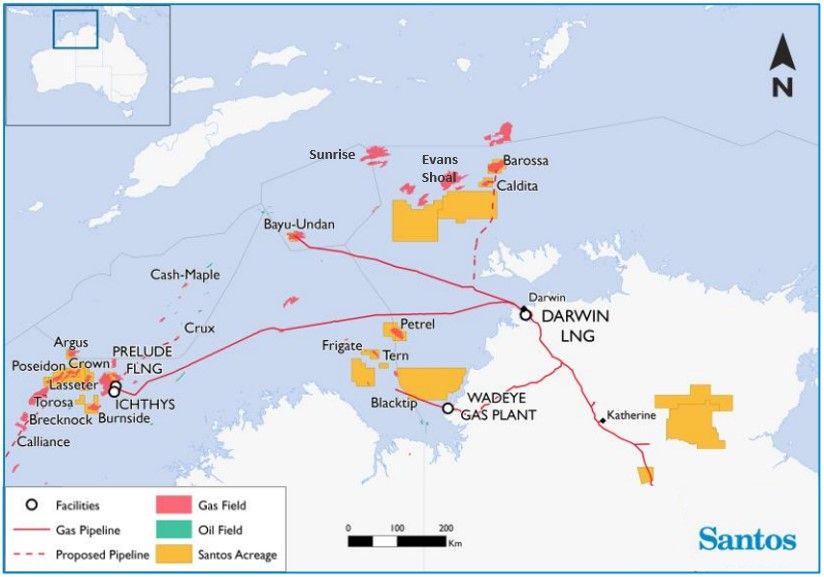

The end of gas production at Bayu-Undan in about 2023 threatened to leave an empty Darwin LNG plant and a massive $US1.1 billion offshore decommissioning bill in Timor Leste. Santos owned 68 per cent of the problem after buying out ConocoPhillips' 57 per cent share for $US1.5 billion in 2019.

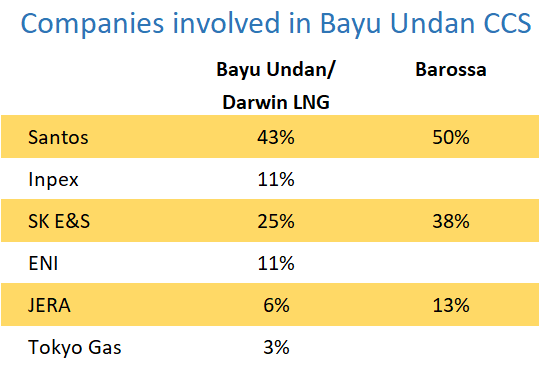

Santos' solution was to fill the plant with gas from its $US3.6 billion Barossa project sanctioned in March. At the same time, the Adelaide-based company reduced its Bayu-Undan equity to 43 per cent by selling down to South Korean SK E&S.

However, with 16 to 20 per cent CO2 in the reservoir, Barossa created another issue: carbon-intensive LNG, which is the opposite of what buyers want and incompatible with Santos' aim of zero net emissions by 2040.

Making a tonne of LNG from Barossa gas will create three times the emissions compared to the Pluto and Wheatstone plants, and Gorgon when CO2 injection works, making Barossa LNG Australia's dirtiest.

The next move by Santos to ensure the ConocoPhillips purchase is not an expensive dud is to store CO2 from Barossa in the soon to be depleted Bayu-Undan reservoirs, simultaneously offsetting emissions and delaying decommissioning by decades.

However, to succeed, Santos must corral a myriad of companies and two governments and overcome technical and economic challenges.

Getting carbon dioxide from Barossa to Bayu Undan is not straightforward.

The Barossa plan underway is for a mix of methane and CO2 to flow through a new pipeline at least 260km long that connects to the existing Bayu-Undan to Darwin pipeline.

Using a section of the existing pipeline saves the Barossa project millions of dollars but cuts off the future route to move CO2 to Bayu Undan.

If Santos goes ahead with Bayu Undan CCS a few years after Barossa, it will have to build a pipeline from Darwin to the disused portion of the Bayu Undan pipeline at great expense.

In Darwin, the CO2 would be separated and compressed to travel 500km to Bayu Undan and injected underground through modified existing wells.

Santos chief executive Kevin Gallagher told investment analysts in August that he could not disclose the cost of Bayu-Undan CCS "because we're working through all of that, except to say, it looks very competitive."

According to documentation seen by Boiling Cold, Santos concluded that Bayu-Undan CCS would cost more than $US1.6 billion ($2.2 billion).

The internal analysis showed that just storing 2.3 million tonnes of CO2 a year from the Barossa reservoir resulted in an excessive cost per tonne.

The project needs additional income from storing four million tonnes of CO2 from Inpex's Ichthys LNG project that has its LNG plant near Santos' Darwin LNG.

Unfortunately for Santos, it is understood that Inpex prefers a storage location near the Petrel field west of Darwin and is progressing CCS at a slower pace than Santos.

Inpex is not the only company Santos has to convince of the merits of Bayu-Undan CCS.

All the Barossa and Darwin LNG/Bayu Undan joint venturers must be on board. Because CCS is not covered in the joint venture agreements, all participants have a veto.

An added complication is Japan's JERA that 18 months ago signed a letter of intent to buy 12.5 per cent of Barossa from Santos and is yet to complete the transaction. The sale is important to reduce the financial load on Santos, but Boiling Cold understands any change to the project puts the JERA deal at risk.

But the Timor Leste government may be the biggest hurdle. It will want revenue from CCS and assurance there will be money available mid-century when the delayed decommissioning of Bayu Undan occurs.

Santos also wants the Australian Government to help. Earlier this week, Gallagher called for the provision of low-cost financing for CCS projects.

The two Governments will need to cooperate in developing a unique regulatory solution that would let Santos produce CO2 in Australian waters, bury it under the Timor Leste seabed, and generate Australian Carbon Credit Units.

Such bespoke agreements with governments and other companies can take years to conclude. With so many parties involved, the risk of one with less at stake than Santos moving too slowly is high.

Simply partially offsetting Barossa and Ichthys' very high emissions is an insufficient economic justification for the $US1.6 billion Bayu-Undan CCS project.

The Santos business case included income from selling carbon credits and the economic value of delayed decommissioning and still predicted a rate of return of less than 10 per cent.

A delay to decommissioning risks ageing infrastructure and increasing regulatory requirements causing a cost increase greater than the calculated economic benefit of delay.

It is understood Santos is finalising an update to the Bayu Undan decommissioning cost to provide to the Timor Leste Government. A higher estimate will increase both the reward and risks of delay.

Santos is considering setting up a new company with other BU participants to own and operate the decommissioning project to reduce its perceived abandonment liability. It would be structured so the decommissioning liability is not reflected on the Santos balance sheet.

The second helper to the Bayu-Undan CCS business case also has complications. The carbon credits cannot be sold to a third party and then also used to market Barossa LNG as having a lower carbon intensity or contribute to Santos' net-zero by 2040 target.

In June, an investment analyst covering Santos said its plans for CCS at Moomba in SA appeared close to double-counting of credits.

Gallagher told analysts in August that there is a "bit of water to go under the bridge" before CCS at Bayu Undan became a possibility.

While BU CCS is under investigation, the company can justify assuming a mid-century decommissioning when calculating abandonment liability.

The project is also part of Santos' efforts to achieve net-zero emissions by 2040 that shareholder activist group ACCR has taken Santos to court over, claiming the target was not credible.

For these two reasons, Santos is unlikely to stop pursuing BU CCS any time soon. But, if it does, Santos has a big clean up bill to pay and a lot of dirty LNG to sell.

Boiling Cold posed a series of questions to Santos. A spokesman for Santos said the company was still early on in the process and therefore couldn’t comment further.

Main image: Bayu Undan offshore gas facilities in the Timor Sea. Source: Inpex.

All the info and a bit of comment on WA energy and climate every Friday