🗡️ Who murdered the Murujuga rock art science?

Special Cluedo™️ edition 🔍 Was it Mr Cook or Prof Smith?

Barossa would produce Australia's dirtiest LNG and if other companies will not back it Santos has a very expensive problem.

ANALYSIS

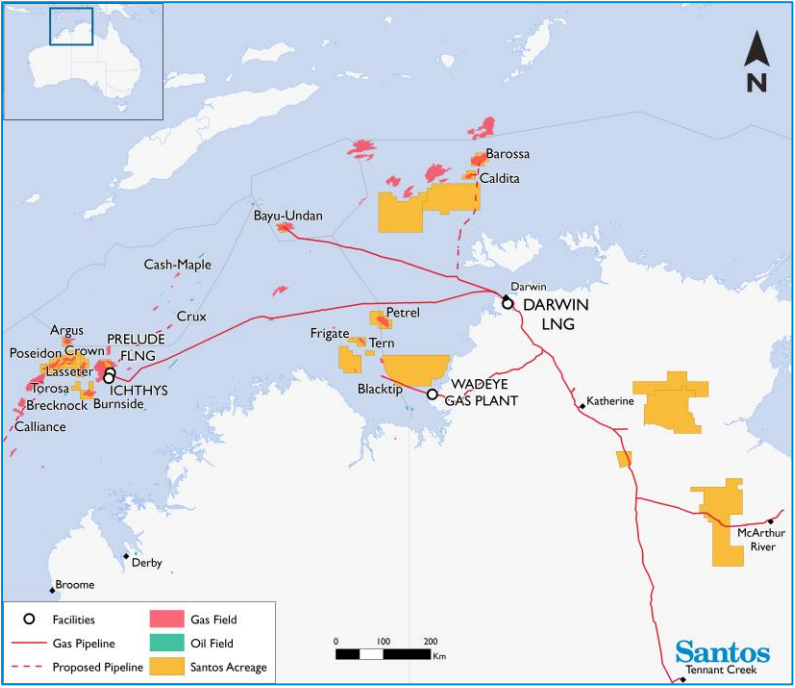

When Santos bought ConocoPhillips northern Australia LNG interests for $US1.465 billion ($2 billion) in October 2019 Brent crude cost $59 a barrel, the LNG outlook was rosy, partners lined up to invest, and the crucial Barossa development was to go ahead in early 2020.

Seven months later when the deal completed Brent cost $US34 a barrel after going as low as $US15, CO2-rich Barossa was delayed indefinitely, and Santos is left holding well more than its target equity of 40% in the assets.

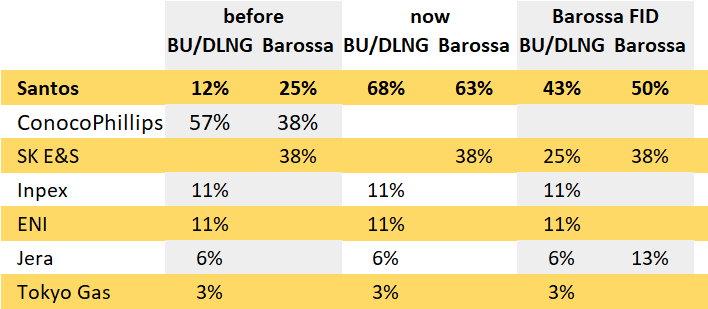

Santos has increased its stake in the Darwin LNG plant and the near-end-of-life Bayu-Undan field from 12% to 68%, and its interest in the Barossa field lined up to supply gas to Darwin LNG from 25% to 62%.

It was another move offshore for the Adelaide-based company that bought Quadrant Energy’s WA operation in 2018 for $US2.15 billion.

Again, chief executive Kevin Gallagher invested in assets that Santos already had a stake in and assumed operatorship.

ConocoPhillips’ large northern Australia headquarters in Perth will join Santos’ WA operation like the Quadrant employees in 2019.

The plan was for Santos to sell down to more closely align the ownership of the Barossa field and the Darwin LNG plant that may soon shut down when gas from Bayu-Undan stops flowing. LNG contracts would be signed and the $US4.7 billion ($6.5 billion) Barossa project given the go-ahead.

South Korean SK E&S has agreed to buy 25% of Darwin LNG and Bayu-Undan for $US390 million, and Japan’s JERA is interested in taking 12.5% of Barossa.

Unfortunately for Santos the SK E&S deal is conditional on the sanction of the Barossa project and JERA have just signed a non-binding letter of intent. For now, Santos is caught holding a very costly baby.

When the ConocoPhillips transaction completed in May Santos made much of the fact that it had increased the portion of the price contingent on Barossa approval from $US75 million to $US200 million, about 14% of the total price.

This was small concession from ConocoPhillips given the financial disaster Santos faces if Barossa does not go ahead.

In that downside scenario, that any company should plan for, Santos would have paid $US1.265 billion to increase its stake in an LNG plant that may be empty in a few years, an offshore facility with a $US1.1 billion abandonment cost, and a field of high-CO2 stranded gas.

The purchase price plus the extra 57% of Bayu-Undan abandonment cost amounts to a $US1.89 billion ($2.6 billion) hit, about 20% of the Santos’ market capitalisation. Abandonment of Darwin LNG would add to the bill.

The financial impact will be considerably lessened by the increased share of Bayu-Undan and Darwin LNG profits that flow to Santos from the January 2019 effective date of the ConocoPhillips deal.

Santos would be in a much better position if it had secured from ConocoPhillips a common clause in large oil and gas deals: if the oil price drops drastically – in this case 42% - between agreeing terms and completion all bets are off.

Boiling Cold understands this clause was bargained away at the negotiation table.

ASX-listed oil and gas junior Karoon Energy struck a much better deal when it bought the Baúna field offshore Brazil. In July Karoon announced that the purchase price of $US665 million agreed in June 2019 had a $US285 million component contingent on increased oil prices.

While Karoon was able to link 43% of its acquisition price to a success case, Santos managed only 14% with ConocoPhillips.

Santos’ agreements to sell down may also be problematic.

SK E&S’s commitment to buy additional equity is conditional on a final investment decision on Barossa, but as a member of the Barossa joint venture it can veto that decision. The deal appears to be an option that SK can take or leave.

Santos chief executive Kevin Gallagher and his counterpart at Woodside Peter Coleman may not, rumour has it, be best of mates but they have a common strategic approach.

Both ambitious men are driven to grow companies that are big Australian players but much smaller and with fewer investment choices than many of their joint venture partners.

The two companies are forced to either take a high stake in a project initially or buy out less interested partners to stop projects being left on the shelf.

Either way, the result is risk and value concentrated in a small number of projects and desperate attempts to push through the few investment opportunities they have.

Woodside’s 90% share in Pluto and Santos’ 80% of Narrabri are examples of investments so good partners could not be found.

Pluto did not have sufficient gas reserves to support a second LNG train that would have justified the high initial investment, and Narrabri may never happen.

Woodside bought an unenthusiastic ExxonMobil out of Scarborough to have an alternative growth option to Browse. It is likely Woodside will now have to buy Chevron out of the North West Shelf to increase its control over where to put that Scarborough gas. BHP is also looking to exit the North West Shelf, and others may follow.

Santos has repeated the process with the acquisition from ConocoPhillips and now faces ENI selling its 11% of Darwin LNG.

If the trend goes too far so much will be spent buying out partners that would rather invest elsewhere there will be little money left for the projects themselves.

The rush of major players out of some or all of their Australian LNG investments should prompt some concern about how good an investment in Australian LNG is.

One thing ExxonMobil, Chevron and ConocoPhillips have in common is that they are shortlisted to invest in the expansion of LNG from Qatar.

The lure is easy to understand given that respected industry consultant Wood Mackenzie estimated Qatar could deliver LNG to East Asia for less than half the price of Woodside’s Scarborough to Pluto proposal. Barossa’s cost of supply was not revealed, but would certainly be closer to Scarborough than Qatar.

Santos has a long list of problems to solve to achieve the plan it bet $2 billion on ten months ago.

History shows that Australian LNG projects go ahead when the equity in the gas fields and the LNG plant are the same.

A misalignment makes agreement on the terms to process the gas into LNG very difficult. The upstream parties want a low tariff and high reliability while the downstream investors seek to minimise both costs and their responsibility for lost production.

Santos is a long way from achieving that alignment, even with its agreements with SK and JERA.

ENI wants to exit Australia so will not invest in Barossa to match its interest in Darwin LNG.

Inpex’s money in Australia is committed to keeping gas flowing to its Ichthys LNG project with expensive drilling and compression projects.

If these companies are more likely to sell than buy, who would step in? Not an investor that puts any weight on climate risk in its decision making.

Barossa has escaped the public scrutiny directed towards Narrabri on the east coast and Woodside’s Scarborough and Browse projects in the west.

However, the Barossa reservoir with 16% to 20% carbon dioxide would concern any investor focused on climate risks: which is just about all of them.

Santos estimated the Barossa offshore development would emit an average of 3.38 million tonnes of greenhouse gases a year in its submission to the offshore regulator NOPSEMA. The Darwin LNG plant emits about 1.66 mtpa of C02, as reported to the Clean Energy Regulator.

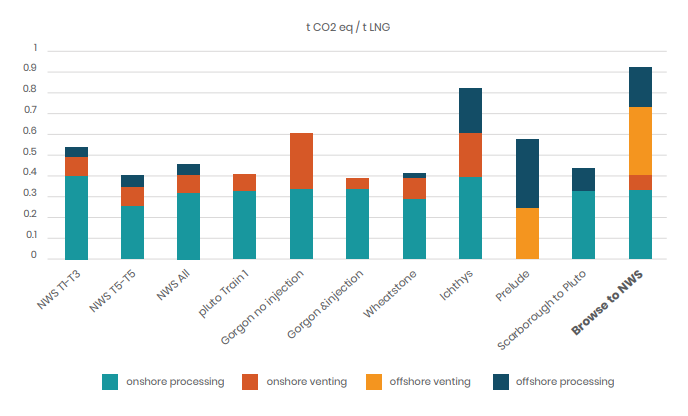

This means each tonne of Barossa LNG from the 3.7 million tonnes a year Darwin LNG plant would send about 1.36 tonnes of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

The carbon intensity of LNG from Barossa is literally off the chart produced but the Conservation Council of WA for its campaign against the Browse project.

Barossa LNG is incredibly three times more carbon-intensive than LNG from Pluto, Wheatstone, or Gorgon if its CO2 injection works.

ConocoPhillips luckily rid itself of the hot potato of Barossa emissions and Bayu-Undan abandonment costs before the pandemic-induced oil and gas price crash.

Santos is now holding the costly smelly package and dearly wants someone to pass some of it onto others.

And those parties know Santos needs a deal more than them, giving them all the negotiation leverage.

Tomorrow morning Santos presents its half-year financial results.

Correction: 22 August: JERA has merely signed a letter of intent to buy an interest in Barossa. The original story reported JERA had agreed to buy a stake subject to a final investment decision on Barossa.

Main image: Bayu Undan facility in the Timor Sea. Source: Santos

All the info and a bit of comment on WA energy and climate every Friday