Gas seeping to surface from Chevron's Barrow Island oil operation

The WA environment regulator is investigating unknown amounts of hydrocarbons rising to the surface on the Class A nature reserve.

Andrew Forrest has put his iron ore miner FMG on a fast track to net-zero emissions by 2030. Achieving high speed on a rocky road will not be easy.

ANALYSIS

When Andrew Forrest set FMG to eliminate carbon emissions from its vast Pilbara money machine in less than 10 years, the move was welcomed not only by environmentalists but also by hard-nosed investment analysts.

Fortescue management made much of the company leading the industry with its net-zero emissions by 2030 target.

However, without fantastic execution, a leading-edge can quickly become a bleeding-edge, with the first mover who went too fast haemorrhaging money.

Apart from some east coast coal fanatics, Australian industry knows it must decarbonise. The stick is to avoid an inevitable carbon cost of some type, and the carrot is capturing new opportunities available only to the cleanest and greenest products.

For Forrest, the prize is tackling the eight per cent of the world's greenhouse gas emissions from making steel.

Green steel uses hydrogen made from renewable energy, not coal, to turn iron ore into steel.

For a genuinely emissions-free product, steel mills must eliminate their own emissions and use iron ore mined without producing emissions.

Forrest wants to tackle steel emissions on multiple fronts.

FMG aims to not only eliminate emissions from its iron ore mining but produce the world's cheapest green hydrogen, develop technology for making green steel with low temperatures, and design ships that run on green ammonia.

Forrest's success with FMG shocked naysayers who thought it would drown in debt. The knockers were influenced by losses many investors suffered from Forrest's Murrin Murrin nickel project that one analyst described as having "significant technology risk."

While FMG aims for a 100 per cent emissions reduction by 2030, conservative BHP targets just 30 per cent.

There will be numerous challenges to overcome for FMG's bold green energy move to continue its success and not be a rerun of the Murrin Murrin horror movie. Here are ten of them.

1. Electrify all you can; hydrogen is a last resort

An emissions-free vehicle harnesses renewable electricity to rotate wheels, but how the energy makes the journey makes all the difference.

For battery electric vehicles, five per cent of the energy is lost getting power to the charger. Another 10 per cent disappears in charging and discharging the battery, and five per cent goes to the inefficiency of powering the vehicle. Eighty per cent of the energy generated by wind or solar is left to move the car.

Hydrogen is a different story. Making hydrogen uses 25 per cent of the original energy, 10 per cent is lost in compressing and transporting it, another 25 per cent is used in the hydrogen fuel cell, and some more in powering the car. Less than 40 per cent of the original renewable energy moves the vehicle.

So a hydrogen vehicle consumes twice the green electricity of a battery one. That means more solar panels, more wind turbines, more expense.

2. Minimise storage with wind

Whether green electricity is stored in lithium-ion batteries or by producing hydrogen, it is expensive. To minimise that storage cost a 24-hour operation without fossil fuels needs around the clock green power, which means wind and lots of it.

Solar panels on any FMG site in the Pilbara would be effective, but wind is different. The enormous amount of wind power FMG needs requires the right location, massive turbines to achieve high-capacity factors and a vast area to space the turbines over.

Access to that much land requires years of environmental studies and approvals, as well as agreements with indigenous groups.

If only someone had started this work earlier?

The Asian Renewable Energy Hub is offering at least three gigawatts of power to the local market on top of its own ambitions to manufacture ammonia.

The Hub could soon have a new investor interested in building a 250km transmission line to Port Hedland.

3. A 2030 target affects business decisions now

FMG is in the final stages of gaining approvals to build a $250 million gas-fired 165-megawatt power station that will emit about 670,000 tonnes of CO2 a year.

The station could be up and running by mid-2022. It will support the troubled $3.8 billion Ironbridge magnetite project that is paused for reassessment after cost and schedule blowouts.

When an achievable schedule for Ironbridge is determined, the station may only have about seven years to operate before net-zero emissions in 2030.

Whether the power station plans are changed during the reassessment of Ironbridge will be the first test of FMG's commitment to its 2030 goal.

Conversation Council of WA director Piers Verstegen said FMG should not build the station.

"That is the kind of action that would demonstrate that the company is truly serious about cutting its pollution and capturing the rapidly emerging market opportunities around carbon-neutral metals," Verstegen said.

4. FMG is racing ahead of equipment manufacturers

FMG's diesel haul trucks produce about 25 per cent of its emissions, and the miner consumes about 640 million litres of diesel a year.

Eliminating this diesel use is FMG's biggest challenge.

Fortescue chief executive Elizabeth Gaines said the next big fleet replacement in 2026 required decisions in 2024 and 2025.

However, some big manufacturers are operating to a different timetable. Komatsu is only starting the development of hydrogen-powered haul trucks this year for practical use in 2030.

In partnership with Williams Advanced Engineering, Anglo American aims to have a hydrogen fuel cell-powered haul truck operating in South Africa by June. FMG is testing large batteries in haul trucks on the same schedule.

The miners can accelerate progress with their own trials, but eventually the original equipment manufacturers like Komatsu and Caterpillar need to incorporate the technology in mass-manufactured units.

Any manufacturer committing in three to four years to supply hydrogen-fuelled haul trucks is likely to want its customer to take much more of the performance risk than for a conventional warranted diesel haul truck.

Locomotive manufacturers will have a similar outlook.

5. Iron ore may have to be mined differently

BHP sees other technologies becoming viable before hydrogen-driven trucks.

For BHP chief executive Mike Henry, one option is to reduce haul truck use with in-pit crushing.

Instead of hauling every tonne of iron ore out of the pit, trucks ferry loads to a nearby crusher, and an electrically-driven conveyor does the rest of the work.

Mining iron ore with no carbon emissions will require more than replacing diesel equipment with hydrogen kit. Every aspect of the pit to port process will be assessed for optimisation.

6. Don't distract the money machine

This decade for FMG is like NASA race for the moon in the 1960s, but with one difference.

The moon was NASA's core business, but FMG still has its original job of shipping iron ore every day, as well as developing and deploying new technology on a vast scale.

The early years of desktop studies and trials should not affect operations.

However, in the second half of the decade, the deployment of novel technology could interfere with the smooth operation of the mining that is bankrolling the shift.

7. The final cuts will be the hardest

FMG could struggle to eliminate the most difficult emissions, particularly maintaining power when the wind is occasionally low for a few cloudy days.

The current gas pipelines, diesel tanks and power stations are likely to be still needed occasionally. It may not be often, but when they are used, it could mean the difference between production and shutdown.

8. Start developing offsets now

"While you would never rule out offsets, it's not what we're planning," Forrest said.

However, planning now might be required to ensure affordable offsets are available to FMG in 2030.

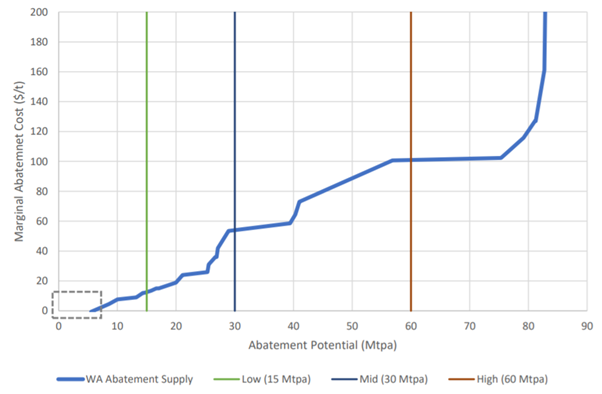

Early movers will capture the cheapest abatement opportunities, a 2018 study of WA carbon abatement opportunities showed.

Woodside has been in the market for years, and Shell acquired a WA carbon farming venture in 2020.

FMG would be wise to prepare for not eliminating all carbon emissions, just in case.

9. An open company culture is vital

In February, a 30 per cent budget blowout at FMG's Ironbridge magnetite cost widely respected chief operating officer Greg Lilleyman and two senior projects leaders their jobs.

A move from shifting ore to processing it was a technical step out for FMG, so problems were likely, and many viewed the management cull as an overreaction.

The complete replacement of fossil fuels throughout the operation in less than 10 years is an order of magnitude more challenging than Ironbridge.

Tens of millions of dollars will be invested in technologies that are found not to work.

After a brief investigation, great ideas will be found to be lacking and need to be killed.

People need to be able to fail, or voice concerns about a proposal, without their careers being damaged.

Quick and open communication will give FMG the feedback loops vital for rapid trialling and decision-making.

10. Culture starts at the top

Forrest's drive is key to FMG achieving net zero emissions by 2030.

However, strong leadership that provides a vision, resources and a challenging deadline can negatively affect the organisation.

Canadian engineer Chris Haubrich looked at why projects were late and over budget in a 2014 study of more than 300 mining projects.

"Once management decides they believe a project is viable, it is hard to change their minds," Haubrich concluded.

"Pressure to advance a feasibility stage project to construction far outweighs the pressure to get the costs right."

In the case of FMG, add the need to get technical feasibility and schedule right.

In some aspects of FMG's race to net-zero emissions by 2030, the cautious tortoise willing to voice concerns will be more valuable than the hare that races ahead on shaky ground.

Andrew Forrest told investment analysts the switch to green energy would be the biggest economic change in their lifetime.

If FMG can get to net-zero emissions iron ore mining ahead of the pack and use that expertise to move into hydrogen more broadly, it is easy to believe FMG could be Australia's biggest company in 2030.

Fingers crossed.

Main image: Andrew Forrest in the Pilbara. Source: Fortescue Metals Group Limited.

All the info and a bit of comment on WA energy and climate every Friday