Five reasons Australia's green hydrogen dream has foundered

Several big green hydrogen projects have been shelved. An expert explains why Australia’s sky-high ambition for the industry is struggling to reach fruition.

Santos and ENI are looking for solutions for CO2 and removing old facilities in the waters north of Darwin. Time will tell if the problems are solved or just delayed.

ANALYSIS

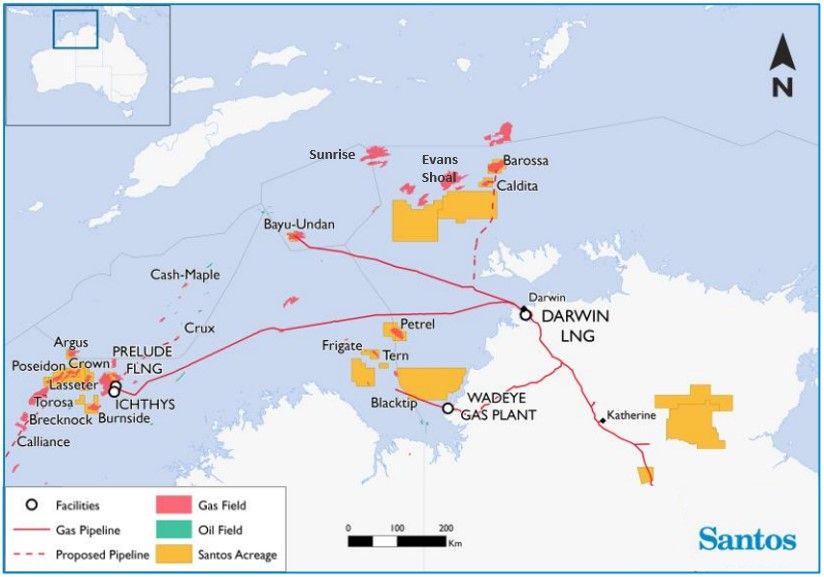

Santos and Italian ENI will work together on two problems they have in common in the waters off northern Australia: gas full of CO2 and expensive cleanups of offshore infrastructure becoming due.

In the past 12 months, the companies came to have shared predicaments in very different ways.

Santos completed the purchase of assets no one else wanted – ConocoPhillips’ equity in the declining Bayu Undan gas field and the Darwin LNG plant.

ENI failed to sell assets it did not want – including Bayu Undan and Darwin LNG – after buyers lost interest when it became clear that decommissioning costs in Australia were becoming harder to avoid.

For years the two companies competed to ensure the field it had an interest in would fill the Darwin LNG plant when gas stopped flowing from Bayu Undan.

In mid-2019, Santos emerged the winner when the Barossa joint venture it owns 25 per cent of won exclusive rights to negotiate with Darwin LNG operator ConocoPhillips.

However, Santos still had a problem: US-major ConocoPhillips wanted to exit Australia, not stay around to develop the CO2-rich Barossa field and decommission the extensive Bayu Undan offshore facilities.

Growth-hungry Santos chief executive Kevin Gallagher went all in and removed ConocoPhillips from the scene by buying it out of Bayu Undan, Darwin LNG and Barossa for $2 billion and tripling Santos’s exposure to Bayu Undan’s decommissioning costs.

Now a Barossa go-ahead was vital for Gallagher. Never mind moving on to Woodside, his position at Santos would have become untenable if the buyout of ConocoPhillips had been for nothing.

Gallagher did get Barossa over the line in March after loading up the project with risk.

Santos increased the lease component and described it as a cost reduction; signed up to sell the LNG at the spot price, leaving it exposed to a volatile market; and committed to Barossa before it finalised a sell down to Japan’s JERA.

While the deal was spun and reported as a huge win, a more sober and independent assessment reached a different conclusion.

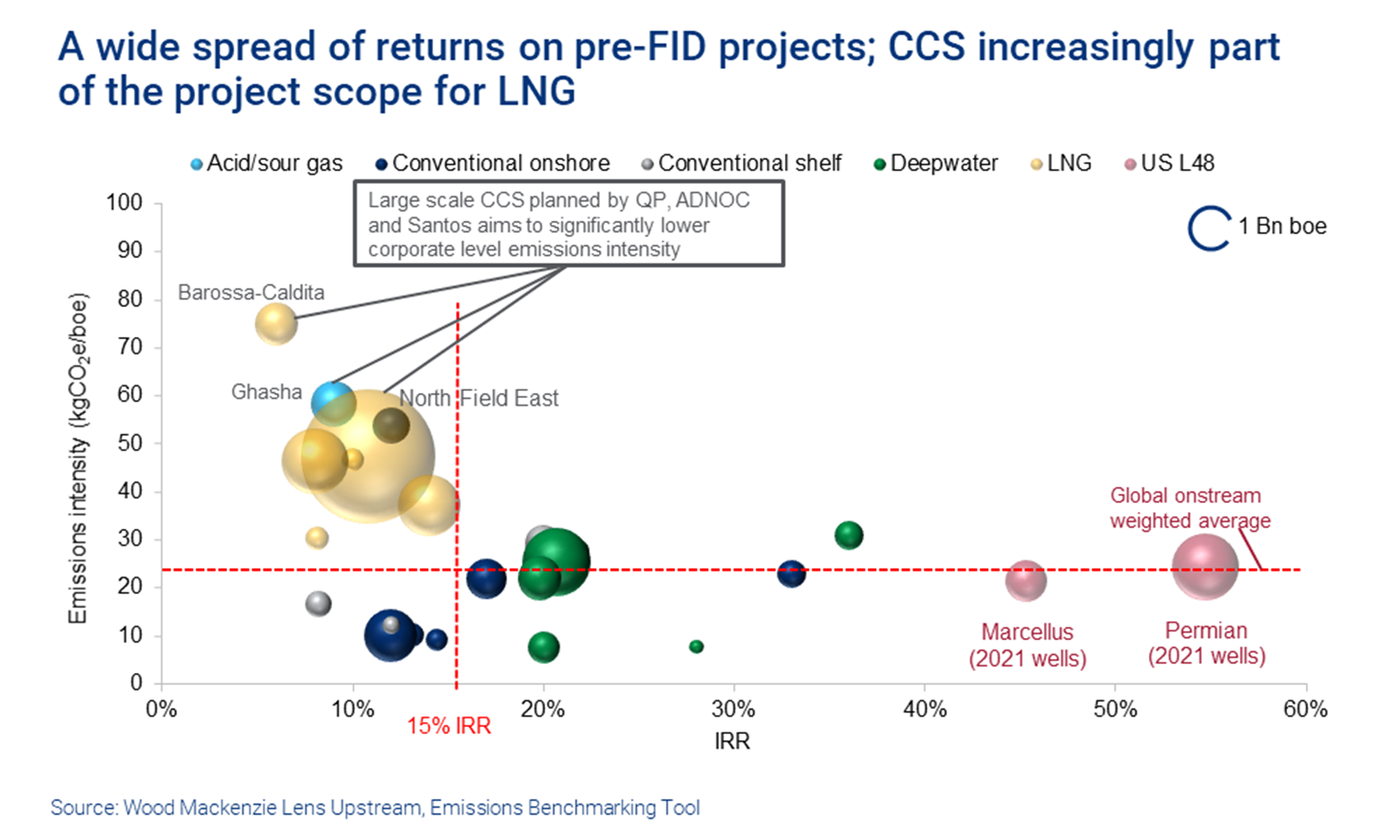

Wood Mackenzie principal upstream analyst Rob Morris analysed 26 global upstream projects sanctioned, or likely to be sanctioned, in 2021.

Barossa achieved the 2021 double wooden spoon award of the lowest return and the highest emissions intensity.

Wood Mackenzie calculated the return of about six per cent with a conservative price for Brent crude of $US50 a barrel, but a higher price would not change the ranking of the projects.

The sanction of Barossa has allowed Santos to defer the decommissioning costs of the Darwin LNG plant.

Santos is left with 43 per cent of the Bayu Undan decommissioning cost of Bayu Undan of about $US1 billion and very dirty LNG from Barossa just when the market is looking for the opposite.

ENI has 11 per cent of the Bayu Undan cleanup bill and the Evans Shoal field that contains up to 30 per cent CO2 and now cannot send gas to Darwin.

The memorandum of understanding between Santos and ENI signed last week positions the companies to grab a share of the Federal Government‘s plan to support carbon capture and storage with $264 million that nominated the Bonaparte Basin as a potential CCS hub.

And those taxpayer’s dollars could help the gas producers solve a few immediate issues of their own.

ENI’s Blackwood retention lease next to Evans Shoal expires in June.

The Italian company must convince the National Offshore Petroleum Title Administrator that the resource could be commercially viable in 15 years or lose the lease. If judged uneconomic, offshore environment regulator NOPSEMA could apply its newly toughened approach to decommissioning and insist wells are plugged and abandoned at great expense.

For NOPTA to judge Evans Shoal and Blackwood viable ENI needs a plan to handle enormous amounts of CO2.

A proposal to send CO2 to the Bayu Undan field for reinjection not only justifies a delay in ENI decommissioning the wells at Evans Shoal, but both companies benefit by pushing back the removal of the offshore infrastructure at Bayu Undam.

Boiling Cold understands the Timor Leste Government supports carbon capture and storage at Bayu Undan as decommissioning costs would be deductible against its royalty income, and it could charge a fee for CO2 storage.

An industry consultant said not all the Bayu Undan facilities would be needed for CO2 injection, so some decommissioning work would not be deferred.

The Barossa project plans to vent most CO2 from the reservoir offshore, but its LNG could be less carbon-intensive if CO2 currently vented at Darwin was instead buried at Bayu Undan 500km away.

Inpex’s Ichthys LNG plant near the Darwin LNG is a potential customer for Bayu Undan CCS, especially when emissions increase by about 30 per cent next decade when Inpex develops a new formation.

In 2019 Inpex dismissed CCS for Ichthys as unaffordable at about $100 a tonne of CO2 but is now revisiting the plan.

ENI, Santos and Inpex all committed to the remote CO2-rich gas off northern Australia when gas was a forever fuel, not a transition fuel, and investors did not consider climate change a business risk.

Now Santos appears stuck in a loop of ever-deepening commitment to the Bonaparte Basin.

First, it bought out ConocoPhillips, complete with substantial Bayu Undan decommissioning costs; then it sanctioned low return and dirty Barossa to justify the initial purchase.

Now Gallagher’s company is chasing carbon storage in deep and distant offshore waters to delay the decommissioning costs of the first deal and partially offset the greenhouse emissions of the second deal.

Chevron has spent more than $3 billion at Gorgon to transport CO2 a few kilometres and inject it underground from onshore wells. The system is yet to be fully operational.

CCS offshore hundreds of kilometres from the source of the CO2 is unlikely to have fewer problems than Chevron’s work on Barrow Island.

If storing CO2 at Bayu Undan is eventually judged to not be feasible Santos and ENI would at least have delayed decommissioning for a few years and temporarily been able to answer the question: what are you doing about emissions?

Main image: Bayu Undan offshore platforms. Source: Inpex

All the info and a bit of comment on WA energy and climate every Friday