🗡️ Who murdered the Murujuga rock art science?

Special Cluedo™️ edition 🔍 Was it Mr Cook or Prof Smith?

Peter Coleman's challenges: an ageing plant, high cost gas, partner churn and global forces making the LNG game tougher than anyone envisaged a few years ago.

ANALYSIS

Chevron's planned exit from the North West Shelf LNG project is the public starting gun for the race for Woodside's future.

In the convoluted and incestuous world of Carnarvon Basin gas, an asset now regarded as optional in Chevron's Californian headquarters is still at the heart of WA's third-biggest company.

All of Australia's LNG players are struggling to develop a strategy for a game with a vastly different set of rules to what they expected when they embarked on a decade-long $200 billion investment splurge.

The new rule book is written by Greta Thunberg, COVID-19, the plunging cost of renewable energy and batteries, and a rampant Qatar seeking to dominate the LNG trade.

It is a game that many of Woodside's partners may choose to play overseas, not in Australia.

Life was simpler when Australia's $49 billion a year LNG industry started with the North West Shelf's first cargo leaving for Japan in 1989.

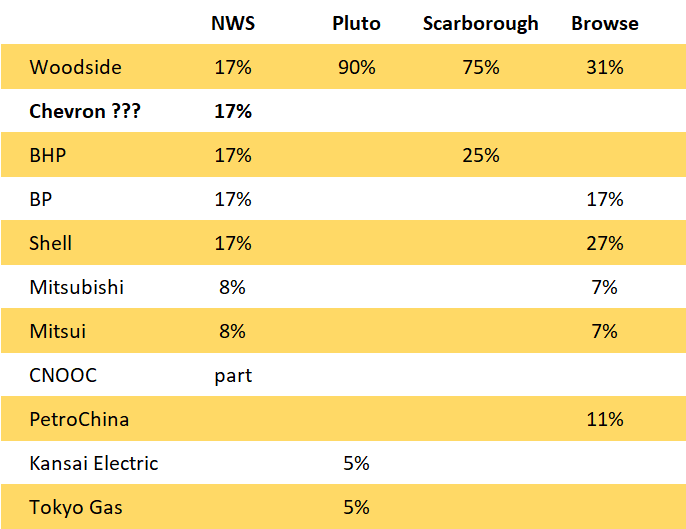

For more than 30 years the six equal partners have remained in the venture: operator Woodside, BHP, BP, Chevron, Shell and Japan Australian LNG owned by Mitsui and Mitsubishi.

The partners invested $34 billion over the years as pipelines and platforms were added to supply more gas to the plant near Karratha that expanded to five LNG trains. The returns on that investment have been huge, but the project's best days are behind it.

Industry consultant Wood Mackenzie expects the NWS will not have enough gas to fill its five trains this year, and the unused capacity will continue to grow.

Woodside chief executive Peter Coleman planned to spend $US20.5 billion to pipe gas 900km from the Browse fields to keep the NWS plant full and increase Woodside's share of the LNG produced.

Browse together with $US11.4 billion to process gas from Scarborough at a new LNG train at Pluto near the NWS plant formed Woodside's Burrup Hub dream to cement its future.

Any NWS partner could veto the plan, but companies with equity in both NWS and Browse were expected to be on board.

Last year Coleman called out Chevron and BHP as the laggards. A public airing of differences is uncommon among oil and gas companies in joint ventures but is consistent with Coleman's robust approach that has won him few friends in industry or government.

Chevron had been clear it wanted to be able to process its gas through the NWS plant. Chevron upstream president Jay Johnson told Wall Street analysts last year he wanted an "interconnected basin with shared infrastructure." Nigel Hearne, the predecessor of current Chevron Australia managing director Al Williams, openly campaigned for access to Woodside's planned Scarborough pipeline.

That strategy is now gone.

Chevron has received "a number of unsolicited approaches from a range of credible buyers" for its NWS stake according to a company spokesperson.

By going public Chevron has signalled it is serious about exiting the NWS and wants maximum competition for its stake.

"Chevron will continue to focus on squeezing maximum value from its large LNG projects, Gorgon and Wheatstone, without the distractions of the NWS," according to Wood Mackenzie analyst David Low.

Chevron's Australian employees are already feeling that squeeze, with job cuts of between 20 and 30 per cent planned.

Woodside's future may continue to centre on a small area of the Burrup Peninsula that houses the NWS and Pluto LNG plants, but international forces will determine its future.

The gas industry happily adopted the label of a transition fuel when that meant moving away from coal. It is not so comfortable with the continuing move away from all fossil fuels.

Australia's LNG mega-expansion was an over-hyped, over-priced, tax-avoiding, low local content, Dutch disease-inducing boom for a world that no longer exists. It has left its proponents with a firmer hold on our governments than their own future.

In Australia, with a gas-obsessed National COVID Coordination Commission, it is easy to forget that much of the rest of the world looks at the fuel very differently.

Just yesterday the International Energy Agency released its plan for a sustainable recovery for the energy sector and gas without carbon offsets did not tick any of its boxes for creating jobs, boosting the economy or reducing emissions.

And it was Woodside that killed the idea of WA producing LNG with carbon offsets when the Environmental Protection Authority pushed it last year.

The market share for gas is squeezed on multiple fronts.

The greenhouse gas benefits of gas over coal have proved much less than earlier thought due to the leaking of methane to the atmosphere.

As battery storage becomes cheaper and demand management more sophisticated, there will be less gas needed to firm up renewable electricity. Consistently low interest rates favour the high capital expenditure but negligible operating expenses of renewable energy.

Within a decade, green hydrogen from renewable energy could be cheaper than using gas and storing the CO2 emitted.

None of this points to gas not being a significant industry for some time, but lower growth and lower prices will push new investment to only the most economic projects.

Many in Australia were bedazzled by the potential, achieved in 2019, for Australia to overtake Qatar as the world's largest LNG producer.

Now Qatar plans to boost its LNG capacity by 40 per cent while Santos and Woodside struggle to keep their LNG plants at full capacity.

Santos' Gladstone plant operates at well under capacity, and its only additional east coast gas is the unpopular and expensive Narrabri development in NSW. The Darwin LNG plant will soon close down due to lack of gas and will wait on the possible sanction of the CO2-heavy Barossa field.

As well as the NWS plant's declining production, gas supply to Woodside's Pluto LNG plant is uncertain without either expensive offshore compression or the Scarborough field.

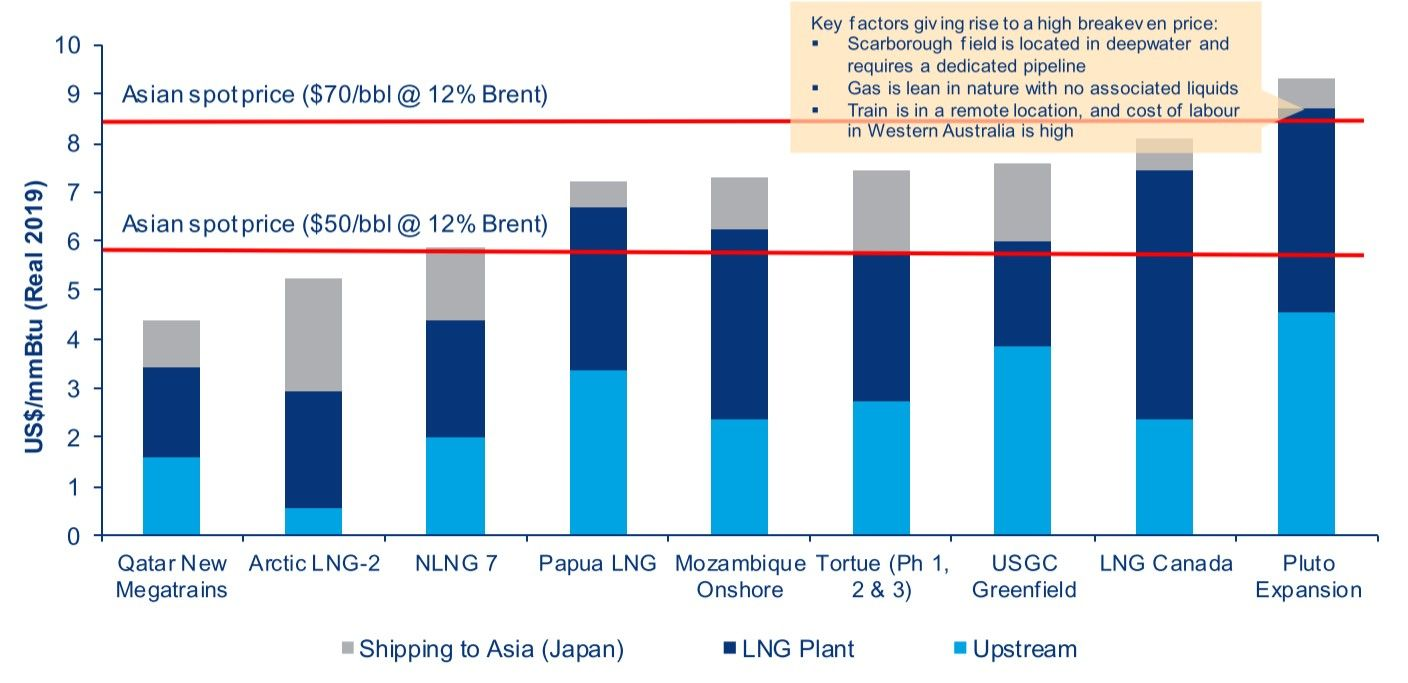

The most economic of these so-called backfill projects in Australia is most likely Scarborough, but Wood Mackenzie ranked it as the most expensive supplier of LNG to Asia of nine competing new projects.

Incredibly, Qatar can deliver LNG to Japan for less than Woodside can deliver unprocessed gas from Scarborough to the beach near Karratha.

Wood Mackenzie's analysis does not mean that Scarborough cannot go ahead, but it will require investors to accept much lower returns than they could get elsewhere. The returns from Browse would likely be even less.

Chevron getting out of the way of Browse going to the NWS will reveal that many of the project's partners apart from Woodside are unenthusiastic.

BP and Shell have both committed to reducing emissions, so why invest in a low-return project to produce LNG more carbon-intensive than any existing Australian project? They have a world of alternatives to choose from.

Additionally, with QGC in Queensland, Prelude and 25 per cent of Gorgon Shell's portfolio is already heavily loaded with Australian LNG.

BP this week set its long-term oil price forecast at $US55 a barrel, well short of Wood Mackenzie's estimate for what Scarborough requires to breakeven, never mind Browse.

If BP and Shell do not want to go with Browse, then they are in the same position as Chevron, invested in an ageing asset with declining production.

Half of the NWS is probably up for sale, perhaps more if BHP decides to offload as well.

BHP has a 25 per cent interest in Scarborough it wants to monetise.

With Browse looking doubtful Woodside will likely move to improve the economics of Scarborough by avoiding a new LNG train at Pluto and processing Scarborough gas through the NWS.

That may be a reason for the big miner to stay or it could decide that its core business is better than the high-risk low-return world of Australian LNG.

Woodside is in a strong financial position to buy more of North West Shelf to achieve the capacity and commercial alignment it needs for Scarborough to proceed.

It is the perfect deal for a company with few options and a seemingly singular strategic vision of "we're an LNG company" as voiced by chairman Richard Goyder's at the AGM in May.

Others will need to think carefully about what they are getting.

Certainly, the $34 billion spent on the project to date has no bearing on its value now. NWS spent $205 million on the Echo-Yodel field, but it could cost $160 million to decommission the subsea infrastructure with additional spend on plugging the wells.

The total abandonment cost will be in the many billions of dollars and could be incurred by the end of the decade if third party gas does not use the facility.

The first three NWS LNG trains are between 28 and 31 yeas old and produce about 70 per cent more carbon emissions per tonne of LNG produced than trains four and five.

The ageing power station is responsible for about 60 per cent of the NOx emissions on the Burrup Peninsula that many worry could damage the extensive Murujuga rock art that is nominated for World Heritage listing. No investor wants to be the next Rio Tinto.

There are plans to build a new power station 20km away, but Woodside has not revealed the cost of that, or the other work required to extend the life of the ageing plant.

The NWS certainly does not fit the standard low-risk criteria of infrastructure investors.

Oil and gas investors will want a sizeable and profitable upstream field to justify investing in the plant, and they seem in short supply.

The six-way NWS joint venture has notoriously always struggled to make decisions, and that was when they all wanted to stay.

Woodside now has a massive task corralling multiple would-be buyers and sellers towards a deal that ends in the final owners of the facilities and gas supply being able to come to a mutually beneficial agreement.

It will help that post-COVID 19 oil and gas majors are making decisions in months that they would typically strategise and workshop for years.

However, it will be next to impossible to get all the participants to agree on a multitude of transactions on one day.

Woodside may be tempted to buy more equity than they want with a plan to sell down later. That approach carries the risk of being left holding the baby if the later transactions do not eventuate.

Kevin Gallagher, Coleman's rival at Santos, is in that position now having bought ConocoPhillips out of Darwin LNG and Bayu Undan with follow-on equity sales dependent on the now-delayed Barossa project.

Recent moves by the Federal Government to tighten foreign investment restrictions will not help, especially with Chinese buyers.

Woodside started the year with a stretch goal of the developing first Scarborough and then Browse.

Now, achieving a more limited ambition of sanctioning Scarborough will be tough.

The permutations are endless, and the challenge of the low margins and commercial complexity of the Carnarvon Basin gas is enormous.

A real option is that it is all too much for prospective investors, and the NWS naturally winds down with no substantial third-party gas processed.

In that scenario, Woodside could use its remaining and substantial Pluto and NWS cashflow to invest elsewhere when assets are cheap.

That would raise two questions. What are Woodside's competitive advantages in the wider oil and gas world, and could its culture cope with being just another small fish in a large and increasingly warmer pond?

Main image: North West Shelf project's Karratha Gas Plant. Source: Woodside Energy Limited.

All the info and a bit of comment on WA energy and climate every Friday