🗡️ Who murdered the Murujuga rock art science?

Special Cluedo™️ edition 🔍 Was it Mr Cook or Prof Smith?

If Woodside's argument that a reef's environmental benefit outweighs 400 tonnes of plastic in the ocean wins over NOPSEMA then leaving everything on the seabed could become the default option for Australia's oil and gas players.

Woodside wants permission to leave all equipment from its Echo-Yodel field on the seabed forever, including almost 400 tonnes of plastic, saving up to $160 million.

The Perth-based gas giant argues that environmental damage from the plastic that will take centuries to breakdown will be outweighed by the benefit from the equipment providing a reef to support marine life.

The North West Shelf LNG project expected the $205 million Echo-Yodel development to produce gas for four to five years from 2001 but the gas flowed until 2012.

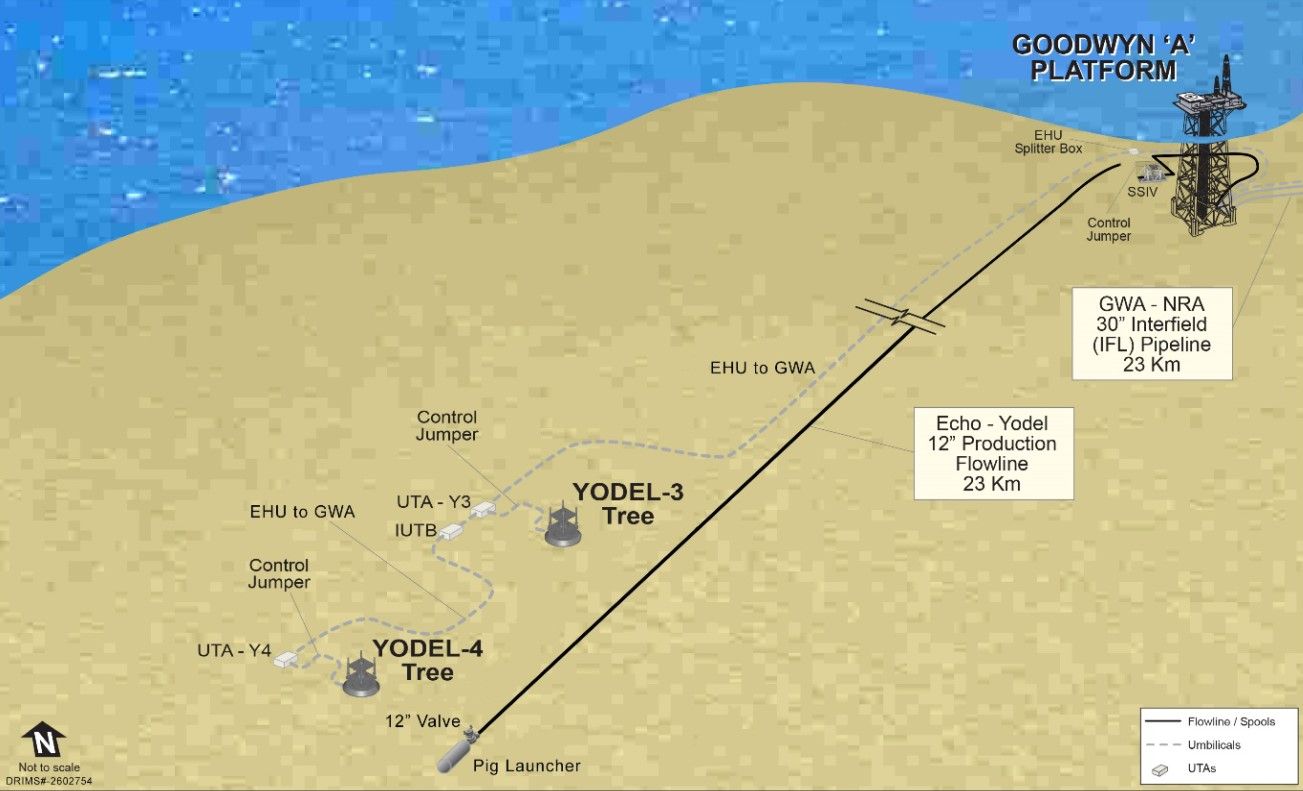

For the past eight years a 23km-long pipeline, a parallel 23-km-long umbilical, two wellheads about 8m high and other equipment have been left on the seabed 130m below the surface 140km from Dampier.

In April Woodside submitted a decommissioning plan to the offshore oil and gas safety and environment regulator NOPSEMA.

Woodside recommended that all equipment be left on the seabed forever. The hardware included 144 tonnes of high-density polypropylene in the umbilical and 247 tonnes of polypropylene pipeline coating.

The plan also included the plugging and permanent abandonment of three wells.

An offshore operator is required by law to remove all structures and other equipment from a title area when it will no longer be used, according to its guideline on the removal of property.

NOPSEMA will only waive this requirement when the operator "demonstrates that the proposed alternative is expected to have equal or better environmental outcomes when compared to removal of property."

NOPSEMA recently signalled a more robust approach to enforcement of this long-standing requirement in response to a direction late last year from then Resources Minister Matt Canavan.

If NOPSEMA allows equipment to remain after production ends the titleholders can relinquish the title and have no future responsibility for what is left there in perpetuity.

The umbilical has enough HDPE to make about 26 million plastic shopping bags.

The Marine Waters joint education initiative between Woodside and the WA Government warns about the dangers of plastic in the ocean:

"For many years, oceans have been a dumping ground for rubbish. With modern society's reliance on non-biodegradable plastics, marine debris is now one of the greatest threats facing the world's oceans."

"Marine debris diminishes in size as it breaks down, so it continues to be ingested by smaller and smaller marine organisms, impacting on marine food webs.

"Increasingly, marine debris is believed to be a source of toxic substances in the marine environment."

Marine scientist Dr Harriet Paterson, who has published four papers on marine plastics, said plastics in the ocean leached chemicals called plasticisers into the water and formed small particles as the plastic deteriorates.

"Plastic and plasticisers are thought to be endocrine disruptors and interfere with estrogen production," Dr Paterson said

Paterson said the plasticisers were probably already leaching into the ocean and had the potential to reduce the reproductive output of fauna, but the process was not yet fully understood.

"While the plastic may make a reef, the outcomes from the chemicals and fragments could be detrimental to the reef over time," Paterson said.

"You can't demonstrate that it is safe at this stage."

Woodside does not mention plasticisers or the leaching of chemicals from plastic in its 816-page plan.

A Woodside spokesperson said the plasticisers in the umbilical did not contain chemicals known to affect oestrogen and plasticisers have been reported to leach at temperatures much higher than those experienced at Echo Yodel.

The spokesperson said Woodside had considered scientific studies that found the subsea infrastructure could continue to provide a significant habitat for marine life over the longer term.

"The studies found that the majority of the Echo Yodel pipeline would self-bury over time, with a very small part of the pipeline degrading over a period of hundreds to thousands of years," the spokesperson said.

"The pipeline plastic is dense and will not float, does not contain toxins, and provides hard substrate that's created an ecosystem to support marine life in a predominantly sandy and barren subsea environment."

Studies commissioned by Woodside predicted that eventually 77 tonnes of the pipeline coating and 29 tonnes of the umbilical HDPE will be dispersed into the environment, about a quarter of the plastic left on the seabed.

Woodside's decommissioning plan for Echo Yodel compared leaving the equipment on the seabed to removing it by ranking 18 socio-economic, environmental, health and safety, technical and economic factors.

The analysis is inconsistent with how NOPSEMA determines if equipment does not have to be removed: can it be demonstrated that leaving the equipment in place results in an equal or better environmental outcome?

The non-environmental criteria considered by Woodside are not relevant.

The best long-term environmental outcome is a balance of the damage to marine life from leached chemicals and plastic nanoparticles from degraded material against the benefit of the equipment supporting marine growth and habitat.

Remarkably little of Woodside's plan addresses the central question of whether removing or leaving equipment on the seabed achieves the best environmental outcome.

In its assessment of the pipeline Woodside weighted the cost of its removal, between $50 million and $100 million, as 27 times more important than the long-term water quality factor used to capture the adverse effects of plastic.

The low importance of the pipeline's plastic coating was in part justified as much of it was buried and the "remainder breaking down immeasurably slowly, starting off in large chunks then into smaller fragments over time, which will have very little measurable impact on water quality or sediment quality."

Woodside ignored that it is the very small size of the plastic particles that causes environmental damage as the fragments are ingested by plankton and then accumulate in animals up the food chain.

Woodside used the same logic to rank the $10 million to $50 million cost of removing the umbilical as eight times more important than the long-term environmental damage from the plastic.

The cost to remove the wellheads was estimated to be less than $10 million.

Equipment should only be left permanently on the seabed in rare cases involving small components of non-polluting infrastructure, according to the Australian Marine Conservation Society.

AMCS spokesperson Paul Gamblin said this should only happen after thorough environmental assessment and engagement with conservation and fishing interests.

Woodside sought feedback from numerous fishing groups in the preparation of the Echo Yodel plan, but not from conservation groups.

Boiling Cold asked Woodside why it did not consult with conservation organisations given the plan stated: "Woodside has sought to…ensure all relevant stakeholders are identified and engaged."

A Woodside spokesperson said the consultation had occurred with relevant stakeholders.

The plan noted comments from an unnamed Pilbara trap fishing license holder consulted by Woodside who supported leaving the equipment on the seabed:

"Plastics in subsea infrastructure may garner negative attention stakeholders and hence believed strong position around value of fish/biodiversity may be needed to balance the argument."

Gamblin said there was a real risk that some companies might seek to reduce costs by exploiting loopholes and leave a degrading industrial legacy on the seafloor.

"Given the multiple, direct threats to fragile marine ecosystems posed by oil and gas extraction, the very least companies must do is clean up after themselves," Gamblin said.

"Governments must uphold and enforce effective regulations and strictly hold companies to their obligations through to the end of a project's life."

Offshore Alliance spokesperson Daniel Walton, who is also AWU national secretary, said Woodside was attempting to dodge its responsibility to clean up after itself.

"It is completely possible to remove it responsibly; it's just that Woodside doesn't want to spend the money and employ the labour," Walton said.

"That's a violation of the company's social license, frankly.

"The economy could really use the employment currently, given COVID-19."

Woodside estimated that the removal of the pipeline, umbilical and wellheads would require almost 7000 workdays, mainly on offshore vessels.

The industry will closely watch NOPSEMA's decision on Echo Yodel.

Since NOPSEMA was given authority over offshore environmental issues in 2012 it has accepted three environmental plans that addressed whether equipment can be left on the seabed forever.

In 2015 NOPSEMA accepted Sinopec's plan to remove all equipment from the Puffin oil development near Ashmore reef, including a 23-tonne manifold, flexible pipelines and umbilicals.

NOPSEMA accepted Woodside's plan to leave the Argus-2 wellhead on the seabed of the Browse Basin in 2017. The next year Woodside was allowed to leave four wellheads on the seabed of the Carnarvon Basin.

Woodside's Echo Yodel plan is the first to propose leaving umbilicals and pipelines on the seabed.

If NOPSEMA accepts that the benefit of a substrate for marine life is greater than the risk from leaching chemicals and plastic nanoparticles it could form a template for other operators to justify an exemption from their current obligation to remove all equipment once production has ended.

Leaving equipment on the seabed has been labelled a "rigs to reef" approach and if accepted could make a significant impact on the clean-up bill for Australia's offshore oil and gas industry.

Energy consultant Wood Mackenzie has estimated that onshore and offshore oil and gas projects in Australia face a $76 billion decommissioning bill over the next 30 years.

NOPSEMA has requested further information from Woodside before progressing its assessment of the plan, a spokesperson for the regulator said.

Echo Yodel is part of the North West Shelf project equally owned by six companies, the operator Woodside, BHP, BP, Chevron, Shell and Mitsui and Mitsubishi's Japan Australia LNG.

Main Image: Woodside's Perth headquarters, Mia Yellagonga. Source: Woodside Energy Ltd

All the info and a bit of comment on WA energy and climate every Friday