Australia's oil and gas industry will create a $76B clean-up bill

It will cost $76 billion to clean up after Australia's oil and gas industry, with a good chunk to be borne by taxpayers, and no one is in a hurry to start the work.

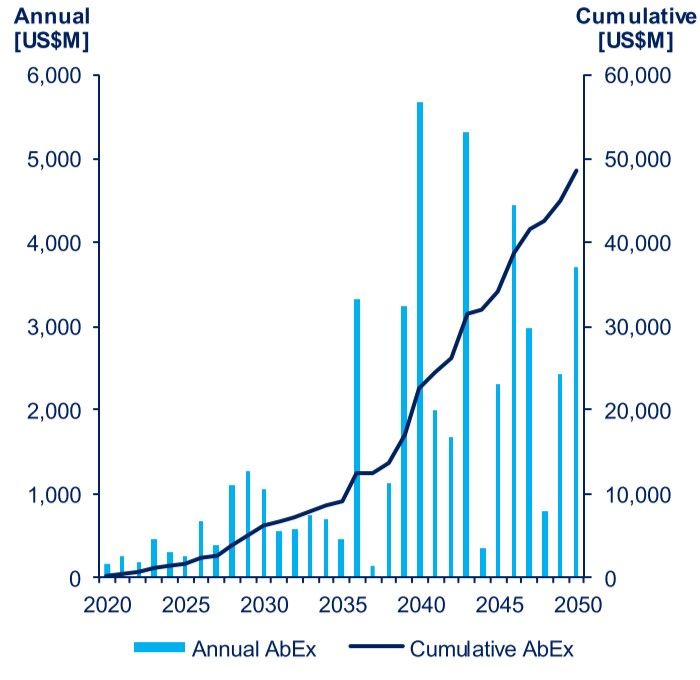

Safely abandoning oil and gas wells, pipelines and platforms in Australia will cost $US49 billion ($76 billion) over the next thirty years, according to industry consultant Wood Mackenzie.

The analysis was revealed in a report commissioned by the oil and gas industry lobby group APPEA that the group has used to call for little change to the industry's tax and regulatory arrangements.

The Wood Mackenzie projection shows an average annual spend of about $1 billion a year up to about 2037. From the late 2030s, the industry will have to spend an incredible $4.5 billion a year.

The costs will continue after 2050. One example is Woodside's North West Shelf LNG plant that the company plans to operate until 2070.

Wood Mackenzie confirmed to Boiling Cold that the estimate covers both onshore and offshore facilities.

The Australian taxpayer could bear up to 58% of the cost of offshore decommissioning as the expense is deductible against company income tax and can invoke a refund from the government of Petroleum Resource Rent Tax paid.

Many offshore projects are unlikely to pay significant amounts of PRRT, effectively getting the gas they produce for free. In those cases, and for onshore facilities, the taxpayer liability will be limited to 30% of decommissioning costs.

The worst-case scenario for Australian governments is if they are left with the entire mess, either after a corporate failure or if an international company walks away from a local subsidiary.

This year Northern Oil and Gas Australia, owner of the Northern Endeavour oil vessel in the Timor Sea, went into liquidation. The Federal Government has taken over the facility and may face a decommissioning bill as high as $230 million.

New Zealand had a similar problem with a floating oil vessel that sits over the Tui oil field 50km from its coast. The operator of the field Tamarind Taranaki went into liquidation in November 2019, and New Zealand may have to bear a clean-up cost of about $US100 million ($155 million).

Tamarind Taranaki was owned by Malaysian Tamarind Resources that says on its website it is "building a profitable, nimble and entrepreneurial oil and gas group."

Tamarind Resources is continuing its other oil and gas activities in New Zealand and Australia unaffected by the failure of Taranaki.

New Zealand Greenpeace campaigner Amanda Larsson said it was common practice for oil companies to use subsidiaries to absolve the parent company of liability.

"This dangerous debacle could have been avoided if the government had required a parent company guarantee or a decommissioning bond," Larsson said.

Delay, delay, delay

In Australia, the common practice is to delay decommissioning expenditure as long as possible.

If the oil price is high, the argument is that the cost of rigs and other equipment and contractors is too high. In an oil price slump as experienced now, when contractors would be available at bargain-basement rates, the industry can claim it cannot afford to do the work.

There is rarely a time that is decommissioning time.

Italian ENI has been taken to task this month by the offshore safety regulator NOPSEMA about its management of the shuttered Woollybutt oil field offshore from Onslow.

Woollybutt ceased production in May 2012 and the floating facility Four Rainbow left a few weeks later.

It was not until 18 months after the shutdown that ENI issued a plan for the decommissioning of just some the equipment that remained. The plan for the final stage of decommissioning, plugging the wells, was accepted by NOPSEMA in July 2019.

The regulator required to work to be completed by July 2024: 12 years after production stopped at Woollybutt.

Delay can increase costs and cause safety concerns.

NOPSEMA found that ENI's annual inspections of the condition of chains that attached large buoyant structures called mid-depth buoys to the seabed had been inadequate and the equipment had exceeded its design life.

The regulator concluded that if the chains holding the MDB failed the buoys could rise to the surface and "would create a marine vessel collision hazard leading to vessel damage or sinking and could result in injuries to, or loss of life of, vessel personnel."

The Federal Government is reviewing the regulation of the decommissioning of offshore facilities.

Onshore decommissioning is the responsibility of state and territory governments.

Note: The Wood Mackenzie report for APPEA shows a decommissioning spend to 2050 of $US49 billion in a figure, but the accompanying text states $US39 billion. Wood Mackenzie has confirmed to Boiling Cold that $US49 billion is the correct number.

Main image: ExxonMobil platform in the Bass Strait. Source: ExxonMobil