Western Gas, an ineffective regulator and a $US100M clean-up bill

If Western Gas' Equus LNG project does not take off in these tough times neither the small company nor regulator NOPTA have an answer to how making safe the wells is paid for.

Cleaning up after Australia’s oil and gas industry will cost $76 billion over the next three decades, and the Federal Government is powerless to stop big gas passing that liability onto smaller companies with less financial strength.

In late 2017 the responsibility to make safe five gas wells in 1000m of water off WA that could cost $100 million passed from the then $US14 billion Hess Corporation to a company formed just weeks before, and the Federal Government had no say in the matter.

For Hess, it was the end of a 10-year $US1.8 billion quest to mimic fellow-American Chevron and develop an LNG project in the Carnarvon Basin.

The deal

Hess Australia Holdings signed an agreement on 26 October 2017 to sell two subsidiaries that owned interests in two offshore titles, WA-518-P and WA-519-P, to Western Gas Corporation Pty Ltd.

Hess Australia’s annual filing with the corporate regulator ASIC noted: “The company sold its investment in the subsidiary undertakings, with total net assets of $US4, for consideration of $US1.”

At the same time, US-based Hess Corporation sold to Western Gas two other Australian subsidiaries that owned the rights to offshore titles WA-70-R and WA-474-P. Boiling Cold understands this purchase price was also $US1.

Western Gas Corporation Pty Ltd was formed just 15 days earlier. For an outlay of $US2 it now had the rights to develop oil and gas from the vast Equus acreage in the Carnarvon Basin.

Western Gas is principally owned by its two executive directors Will Barker and Andrew Leibovitch who, through several companies, own 32.5 per cent of Western Gas each. Barker has more than 20 years’ experience in oil and gas including with Arrow Energy, and Leibovitch is a veteran of Woodside.

AGG WA Pty Ltd, a company with 26 shareholders, owns another 30 per cent of Western Gas and Hong Kong-based Sweet Iron Investments owns the remaining five per cent.

The project

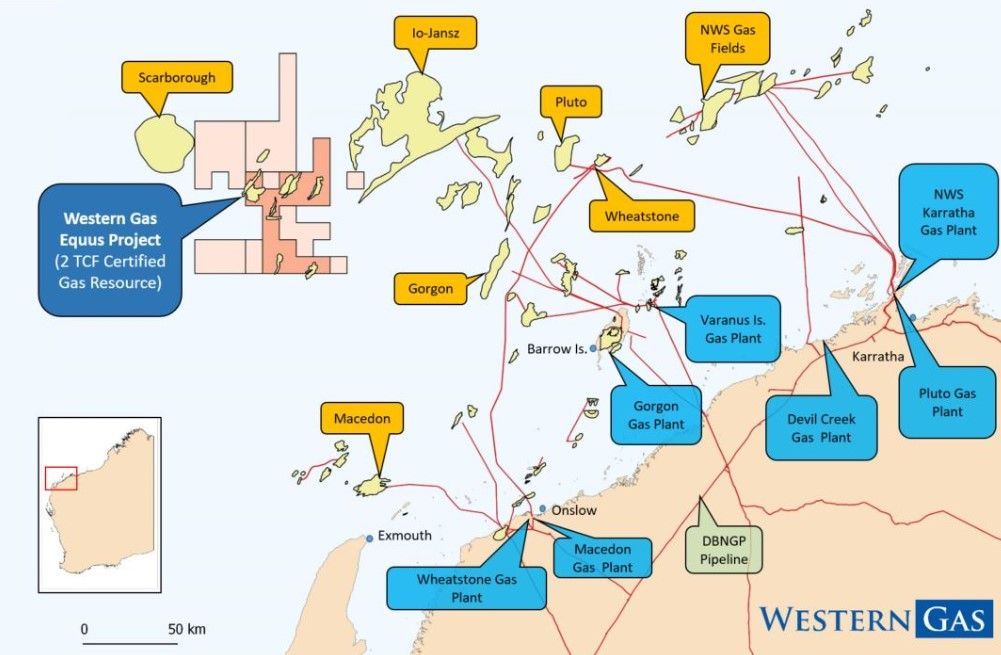

Western Gas plans to develop only the better fields discovered by Hess to decrease the unit cost of gas compared to the American’s plan.

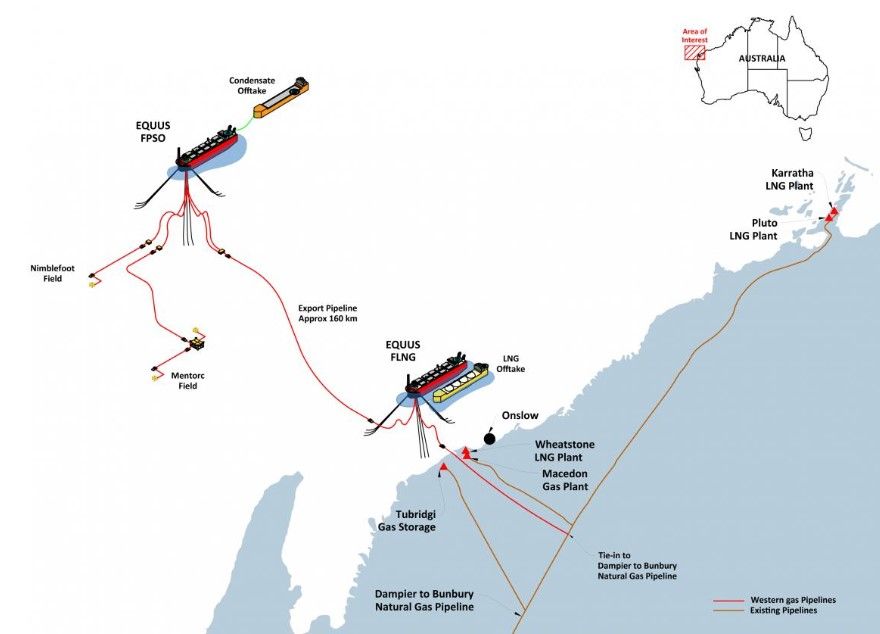

Oil and gas would flow from subsea wells to a floating production facility that offloads oil to tankers. A 160km pipeline would take gas to a floating LNG facility near Onslow with some gas delivered to the WA market.

Leibovitch said in early 2019 that the project would cost between $US3billion and $US4 billion.

A Western Gas spokesperson said the plan could also provide gas to existing LNG plants or the petrochemical industry. The North West Shelf LNG plant will soon have spare capacity.

Western Gas enlisted oil and gas engineering heavyweights McDermott and Baker Hughes to perform the design.

Goldman Sachs is leading a process to attract investors, the Western Gas spokesperson said.

“Equus is an attractive development opportunity with a certified low CO2 resource of 2 trillion cubic feet of gas and 42 million barrels of condensate, a development plan that supports delivery of low-cost gas and with a 20-year project life provides the ability to offer long-term supply contracts,” the company spokesperson said.

Developing an LNG project is always extraordinarily difficult, even for large companies. Finance, customers, partners and engineering contractors must all be on board for an expensive long-term commitment.

After the COVID-19 oil price collapse, Australia’s LNG heavyweights Woodside and Santos both delayed LNG projects. For an industry minnow, the challenge is enormous.

The wells

Hess drilled 21 wells in the waters off WA and before it sold the titles to Western Gas made all but five of the wells safe by the process called plugging and abandoning.

If the Equus project goes ahead, those five wells are a tremendous asset as they can produce gas without the cost of additional drilling.

However, if Western Gas cannot develop the Equus fields, it must make the wells safe before it hands the titles back to the Federal Government.

An asset if the project succeeds, turns into a liability if it does not.

In the UK sector of the North Sea the cost to plug and abandon five subsea wells could range from $45 million to $170 million, with a mid-cost of $64 million. The UK Oil and Gas Authority calculated this range from the cost of 26 wells abandoned in the northern and central North Sea in 2018.

Offshore work in Australia usually is more expensive than the North Sea and one experienced offshore engineer told Boiling Cold he expected it would cost at least $100 million to plug and abandon the five Equus wells.

Boiling Cold asked Western Gas and the National Offshore Petroleum Titles Administrator how the expensive process of making the five wells safe would be paid for if the Equus project did not go ahead.

NOPTA manages the titles the Federal Government awards to companies to explore for and produce oil and gas in the waters off Australia.

In their responses, both the company and regulator pointed out that the development was being progressed.

Neither party addressed the question asked: what happens if the Western Gas does not attract sufficient investors and customers to its Equus project?

The Northern Endeavour

The Federal Government is currently saddled with the cost of one failed offshore company.

In 2016 Woodside paid Northern Oil and Gas Australia $24 million to take its subsidiary Timor Sea Oil and Gas Australia. NOGA was formed eight months earlier.

TSOGA owned the Northern Endeavour oil production vessel and the titles to the Laminaria-Corallina oil field.

Four years later NOGA was liquidated, and Australian taxpayers are responsible for a clean-up that could cost $230 million.

Minister for Resources Keith Pitt announced in April that the Northern Endeavor would be kept safe in so-called “lighthouse mode” at taxpayer’s expense while a longer-term solution was developed.

The Laminaria and Equus deals have a good deal in common: a large established oil and gas company offloads a subsidiary with substantial abandonment liabilities to a new small single-asset company.

The actions of Woodside and NOGA were legal, as were the Hess and Western Gas transactions.

Western Gas, with its engineering partners, could have the required technical capacity to develop Equus.

Western Gas could also have the required financial capability, but this cannot be independently determined as it is below the size required for Australian companies to submit publicly available annual reports to ASIC.

However, the capabilities of Western Gas were not verified by NOPTA that, according to its most recent annual report had the job of “Contributing to national prosperity through administering a thriving offshore oil and gas industry.”

The quick tick regulator

A month after the Hess deal Western Gas told NOPTA that the names of the four companies it bought had changed. NOPTA registered the changed names.

Giving a tick to a name change was the full involvement of the Federal Government in a transfer of significant rights and responsibilities between two completely different companies.

NOPTA has the authority to assess the financial capacity of a company when a title is transferred or an exploration permit is awarded, according to a spokesperson for the Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources that NOPTA is part of.

“As the transaction…occurred at the company level, there was no transfer of title,” under the legislation the Department spokesperson said.

It is common practise in Australia for oil and gas companies to have a myriad of subsidiaries so interests in different projects, or in the case of Hess at Equus even interests in various fields in a project, are held in separate companies.

NOPTA awards titles to these subsidiaries so the ultimate ownership and control of a title can change by selling the company with no involvement of the regulator.

Oil and gas joint venture agreements often guard against the sale of a company in the venture to a perhaps unsuitable owner with change of control provisions.

The provisions give other venturers the same rights as if the company in the venture was sold: such as a veto of the transaction or the right to pre-empt the deal by buying the interest at the same price.

The joint venture can protect itself from the entry of a company that may not be able to pay its way.

Under current legislation, the Federal Government has no such ability to protect the interests of Australian taxpayers.

Is change coming?

The Department spokesperson said current legislation placed a duty on titleholders to maintain sufficient financial assurance to meet the costs required.

“NOPTA regularly meets with titleholders in relation to the progress and performance of projects,” the spokesperson said.

“The Department also works with NOPTA and NOPSEMA (the safety and environment regulator) to keep itself informed on matters impacting on projects.”

Despite these activities, the Government does not have a cost estimate for plugging and abandoning the Equus wells.

The Department spokesperson said a review of the current decommissioning policy and legislation is underway “including ensuring there is sufficient coverage for all decommissioning activity including the plugging and abandoning of wells and providing ongoing monitoring of the financial health of companies.”

The Department plans to release a revised decommissioning framework in the coming months.

“Decommissioning obligations, including the plugging and abandonment of wells, are the responsibility of the registered holder of the title, it must ensure its obligations and liabilities are met,” the Department spokesperson said

“Failure to comply with the property removal, maintenance or repair obligations may attract a criminal or civil penalty.”

Main image: Schematic of Equus field development proposal. Source:Western Gas