Five reasons Australia's green hydrogen dream has foundered

Several big green hydrogen projects have been shelved. An expert explains why Australia’s sky-high ambition for the industry is struggling to reach fruition.

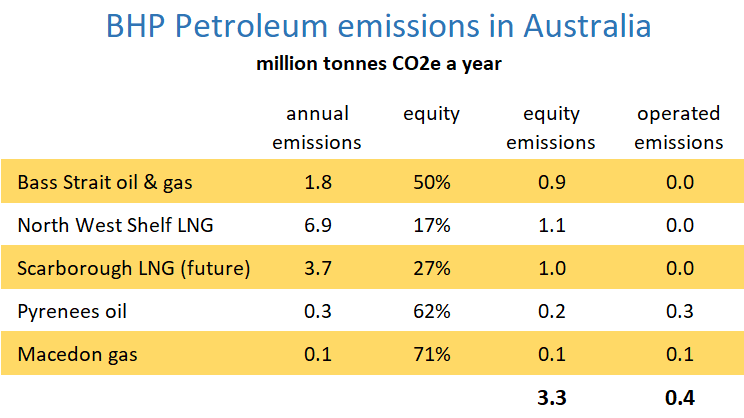

BHP's climate target excludes the Bass Strait, North West Shelf and future Scarborough LNG on the incorrect basis that the operator controls the emissions, not the joint owners.

ANALYSIS

Late this year, BHP's board will meet to determine if Woodside's $US11.4 billion Scarborough LNG project goes ahead.

BHP will need to pay about $US1.4 billion for its 26.5 per cent share of offshore construction and make a long-term commitment to process the gas through an expanded Pluto LNG plant.

BHP's partner Woodside is desperate for Scarborough to go ahead as production from its current projects will decline this decade, and it has no growth options more viable than the economically marginal Scarborough.

However, without BHP's consent and money, the Scarborough project cannot happen.

Unlike Woodside, the diversified miner has an array of choices of where to invest, including copper and nickel that are on a roll to feed the electric vehicle boom.

While climate concerns have left Woodside stuck producing a transition product, it has gifted BHP massive long-term opportunities.

The BHP board chaired by Ken MacKenzie will decide on Scarborough based on work by the petroleum business unit led by Geraldine Slattery that would have been carefully reviewed by chief executive Mike Henry.

Concerns will include the risk of cost and schedule blowouts, the LNG market outlook and how the investment stacks up against alternatives.

Incredibly, in 2021, Henry, Slattery and the BHP board will not have to worry about the 3.7 million tonnes of greenhouse gases Scarborough will emit each year, because in BHP's carbon accounting Scarborough does not count.

That is fortunate for Henry and Slattery as their bonuses are tied to BHP cutting its operational emissions 30 per cent by 2030.

The key word is "operational."

BHP counts all the emissions from projects it operates but ignores the climate impact of its investments in projects managed by other companies.

BHP counts all the 2.5 million tonnes a year of emissions from iron ore mining in WA, despite other companies owning about 14 per cent of the operation.

Conversely, emissions from the giant North West Shelf LNG project that BHP has a one-sixth stake will not affect BHP's climate metrics as Woodside operates it.

BHP target to cut its measured emissions by 30 per cent this decade on the road to net-zero emissions by 2050 needs a reduction of 4.8 million tonnes in annual emissions.

This colossal challenge would be incredibly more difficult if BHP added the extra one million tonnes a year of carbon emitted to make its share of LNG from Scarborough that it will sell to the world.

To measure their climate impact, companies can either tally the projects they operate, as BHP has done for many years, or total the equity share of all projects they have a stake in.

BHP reports its emissions according to The Greenhouse Gas Protocol that allows both approaches. Neither are perfect when applied to the shared responsibilities in the joint ventures that dominate oil and gas production.

In a joint venture, one participant is appointed operator and is paid to manage the asset on behalf of the other companies that cede any involvement in day-to-day activities. However, these non-operating participants still exert significant control as they must approve the operator's annual work program and budget and any significant investments.

For BHP's Australian petroleum assets, the operational control approach results in only the relatively small emissions from the Pyrenees and Macedon projects off WA affecting its climate targets. The huge Bass Strait and North West Shelf projects that BHP has been involved in since they were founded decades ago do not appear on BHP's climate books.

Overseas BHP Petroleum has a mix of operated assets it owns less than half of that appear in its carbon accounting and equity in non-operated assets that do not.

A BHP spokesperson said reporting emissions and setting reduction targets only for the assets it operates was a common practice across the industry that ensures emissions are not double-counted.

In reality, the operational control approach is not close to being an industry standard, and the problem is not excessive counting but the inadequate allocation of responsibility.

BHP has ceded all climate responsibility for the North West Shelf to operator Woodside, but unlike BHP, Woodside bases its targets on its equity share that is only one-sixth of the project.

Targets determine decisions, as was demonstrated when Woodside committed to offset its share of CO2 in reservoirs vented to the atmosphere. What about the other five-sixths of reservoir CO2 from the North West Shelf? No action. Lost in the confusion of carbon accounting.

Other companies that measure emissions by equity interest, like Woodside, are Chevron and Shell.

So much for an industry standard.

Similarly, in the Bass Strait, BHP's view of the world is that it does not have to worry about emissions because operator ExxonMobil will. Unfortunately, ExxonMobil has no targets to reduce its total emissions, only its emission per unit of production.

In 2020 BHP received $US2.2 billion in revenue from the NWS and Bass Strait but passed responsibility for the project's climate impacts onto operators with misaligned objectives. Woodside publicly and clearly only targets its own emissions, and ExxonMobil has climate targets that fall far short of BHP's.

A focus on the company that operates an asset does not reflect who really makes the big decisions that determine emissions.

The operator can alter how the plant is run and maintained to perhaps change emissions by a few per cent. However, decisions with a significant impact on climate – project go ahead, expansions, major capital expenditure to reduce emissions, and abandonment – are made by all the joint venture participants.

Corporate metrics exist to encourage management to make the right decisions. Most metrics push shareholder wealth, but climate metrics should encourage management to minimise the climate damage done by the company.

Under BHP's climate targets, the board and management have no incentive to consider climate impact when the miner effectively will decide if the $US11.4 billion Scarborough project goes ahead or not.

Conservation Council director Piers Verstegen said the community and shareholders expected greater transparency.

"BHP has escaped public attention on these issues to date because they have been able to conveniently hide the full extent of pollution from their fossil fuel investments," Verstegen said.

"That is not likely to be a successful strategy for BHP into the future,

"Committing to cut carbon pollution from one part of your business while allowing it to increase rapidly in another area is simply not a credible approach to climate change."

Australasian Centre for Corporate Responsibility climate director Dan Gocher said BHP cannot continue to sanction projects where it doesn't have operational control, like Scarborough, and think its shareholders will continue to ignore the emissions from those projects.

"BHP's climate commitments are already well behind those of its peers, including Fortescue and Glencore, yet it plans to sanction multiple new oil and gas projects," Gocher said.

"The new IEA Net Zero report confirms that these projects are simply not consistent with a safe climate."

Main image: Graphic of the proposed Scarborough offshore facility with text and BHP logo added. Source: Screenshot from Woodside video.

All the info and a bit of comment on WA energy and climate every Friday