Regulator shuts Wandoo oil field off WA after spill

Canadian firm Vermilion judged the chance of the December spill as "rare" - the same probability it claims for seven planned exploration wells that could affect anywhere along the Pilbara coast.

Shell's giant $US17B Prelude floating LNG is late, expensive, dirty and so far unreliable. An exclusive look at how a failed investment for Shell is a terrible deal for Australia.

ANALYSIS

Shell's Prelude floating LNG facility off the WA coast was to be the first of many that would open up stranded gas reserves around the world thanks to the technical and project management prowess of Anglo-Dutch oil and gas giant Shell.

It has not turned out that way.

When the 488m-long giant arrived in Australia almost three years ago, Shell expected to receive cashflow from the Prelude in 2018.

While the Prelude did export LNG at about half its capacity for the second half of 2019, it is now idle.

Moored far off the Kimberley coast it is plagued with technical problems, dwindling gas reserves and safety processes condemned by the regulator despite Shell and its partners spending about $US19.3 billion ($A30.0 billion) to the end of 2019.

Neither Shell and its partners nor Australia have gained anything near what they expected from the giant experiment.

Cost overruns, delays and to date unreliable production means investors in Prelude are unlikely ever to pay Australia for the gas they export as the payment is linked to profit. Company income tax related to Prelude, if any, will be minimal.

The Prelude also used negligible local content during construction and is making a significant contribution to Australia's greenhouse gas emissions.

Shell has escaped scrutiny over Prelude's cost by not issuing an estimate when the project was sanctioned or supplying updates during construction.

Shell chief executive Ben van Beurden was asked about the cost of Prelude in 2018.

"We don't disclose cost on projects, so I'm also not in a position to disclose whether it is any different to what we have previously not disclosed and I don't want an make an exception in this case," van Beurden said.

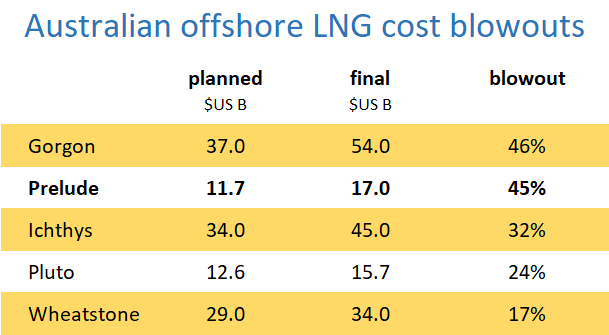

However, when Prelude was sanctioned in 2011 then Shell executive director of upstream international business Malcolm Brinded said the cost would be around $US3 billion to $US3.5 billion per million tonnes of LNG capacity. So Brinded expected Prelude, that should produce 3.6 million tonnes of LNG a year, to cost between $US10.8 and $US12.6 billion: an average of $US11.7 billion.

The cost of Prelude to date may be $US19.3 billion, according to the 2019 accounts of OPIC Australia Pty Ltd, a subsidiary of CPC of Taiwan, that owns 5% of Prelude.

OPIC said construction costs had "totalled US$964 million as at December 2019" for its 5% share, indicating a 100% cost of $US19.3 billion.

Comparisons of costs are not straight forward. Differing accounting policies covering foreign exchange and other issues muddy the waters. The $US329 million spent by OPIC in 2013 to join the project Shell sanctioned in 2011 may have covered some pre-sanction activities such as exploration and front-end engineering design.

However, the OPIC accounts do indicate that the cost estimate of $US17 billion ($A26 billion) from respected oil and gas consultancy Wood Mackenzie widely reported last year was reasonable.

Operators of all the other recent LNG projects offshore WA issued both initial cost estimates and the final cost. A comparison using Wood Mackenzie's estimate shows that Prelude's 45% cost overrun puts it in the same league Chevron's notoriously troubled Gorgon project.

While the Prelude was designed to weigh as much as six large aircraft carriers, its construction cost was not expected to be more than that for three new Australian submarines.

Shell's 67.5% share of the cost overrun is $US3.6 billion: substantially more than the estimated $US2 billion Shell has spent since 2016 moving to lower-carbon energy.

Prelude is one of three attempts by Shell to deploy off Australia the floating LNG technology it started developing about 25 years ago.

Woodside embraced partner Shell's floating LNG technology for the Sunrise field in 2001 after it failed to gain access to ConocoPhillips' pipeline from Bayu Undan to Darwin.

Browse, another Woodside-operated project with Shell as a major partner, chose floating LNG in 2013 after plans to build an onshore plant on the Kimberley coast collapsed. Three years later, Woodside dropped the $US40 billion project.

Shell committed to build a floating LNG facility for its 100%-owned Prelude field in 2011. Later it sold interests to Japan's Inpex (17.5%), Korea's KOGAS (10%) and Taiwan's CPC (5%).

Shell partnered with Technip to design the facility in France and Malaysia and Samsung to construct the giant in its Korean shipyard. The Prelude facility was due to be delivered to the field off the Kimberley coast in 2015, and first gas would flow in 2016 according to the Prelude environmental impact statement.

Combining the world's largest floating structure and a complex and novel LNG plant was an enormous design and construction challenge that did not go smoothly.

The Prelude arrived in Australian waters in July 2017 – 1½ years late – but it was not the end of the problems.

"It's like an offshore platform, and a bunch of pipelines, and an onshore LNG plant, and a storage facility, and utilities, and a hotel for 300 people, and a port, and all of that on a floating facility," Shell vice president for Prelude Rob Jager told The West Australian in 2019.

"Its individual parts in and of themselves are not hugely complex but putting it all together in a confined space is what makes it challenging," Jager said.

Prelude shipped its first cargo of LNG in June 2019 but has not had a smooth ride since.

The LNG produced is reported to be unsuitable for some markets as it contains too much ethane.

Transferring LNG between the Prelude and an LNG carrier alongside through rigid loading arms that contain the -160℃ liquid has proven complex.

In January offshore safety regulator NOPSEMA banned many maintenance activities until Shell fixed its procedures for the safety-critical isolation of equipment before maintenance. NOPSEMA said there was a "significant risk to the health and safety of persons at the facility."

Weeks later the Prelude's problematic steam-driven power system failed again, but this time the diesel back-up generator did not power up. Basic amenities such as toilets stopped working, and Shell quickly reduced the number of crew.

Shell had chosen steam-fired power due to its "proven high reliability in a marine setting" instead of gas turbines that are less polluting and more common offshore.

The Prelude is currently not in production with a reduced crew due to COVID-19 concerns.

Boiling Cold understands designer Technip has still not entirely handed over responsibility for the Prelude to Shell. The construction contract requires a Performance Test Report that demonstrates the Prelude has run at full capacity for 72 hours for Technip to complete its commitments.

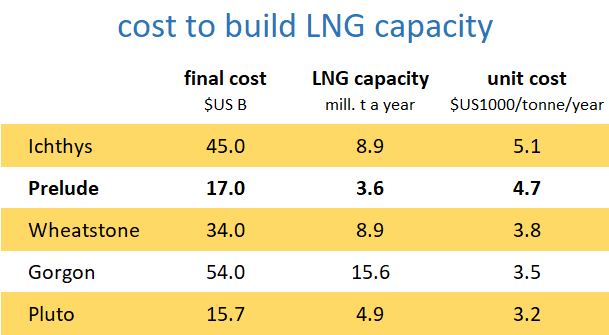

Cost overruns have made Prelude an expensive piece of kit to produce LNG compared to all the recent Australian offshore LNG projects except nearby Ichthys.

Shell said floating LNG would have significant cost benefits over land-based Australian projects when asked by a WA Parliament inquiry into floating LNG in 2013.

CPC's Australian subsidiary has recorded total impairment losses of $US377 million to the end of 2019 on its investment of US$964 million: a write-down of 39%.

Between the first cargo in mid-2019 and the shutdown in early 2020 Prelude was producing LNG at about half its design capacity. A late start-up or a slow ramp-up to full capacity typically hurt investors in two ways – more spending and less revenue.

Prelude is suffering from the delay in a third way: it is losing gas reserves to the Ichthys facilities about 20km to the south. The two projects have separate adjacent petroleum titles, but a line on a map does not impede the flow of gas through a reservoir.

The Inpex-led Ichthys project has drilled subsea wells just 3.5km from Prelude's wells. They are understood to tap the same accumulation of gas and to be enjoying the early high production wells can achieve before the pressure in the reservoir subsides.

When Shell sanctioned Prelude it planned to tap the nearby Concerto field next. Later, Shell decided it was necessary to develop the Crux field 160km away instead of Concerto. Shell has now delayed the sanction of Crux planned for 2020 after the recent collapse in oil prices.

Prelude's inability to operate reliably at full capacity has delayed the need for more gas.

Shell's decades-long development of floating LNG that consumed more than 1.6 million hours of design was not meant to end this way.

When Shell approved Prelude in 2011 chair of Shell in Australia Ann Pickard said: "this will be a game-changer for the energy industry."

Brinded said Shell's ambition was to develop floating LNG projects across the globe.

"Our design can accommodate a range of gas fields, and our strategic partnership with Technip and Samsung should enable us to apply it progressively faster for future projects," Brinded said.

The oil and gas PR machine went into overdrive. In 2017 the University of WA produced a "study" with oil and gas lobby group APPEA called FLNG The Floating Phenomenon.

UWA vice-chancellor Dawn Freshwater in the report's introduction said "FLNG remains a strong candidate for the next generation of gas projects" and Australia's challenge was to "ensure we remain at the forefront of innovation."

But Australia had little input into Shell's floating LNG innovation and even less into building the giant Prelude facility.

The cost, schedule and reliability failures of Prelude, with its very low Australian content in design or construction, should finally put an end to the myth that the problems with recent Australian LNG projects originated in Australia.

The recurring themes have been issues missed in the design phase done mostly overseas and problems with facilities built in Asian shipyards that must be corrected when they arrive in Australian waters.

Chevron chief executive John Watson said in 2017 that the US giant should have done additional engineering work and had more robust plans before approving the Gorgon project in 2009. The company attributed delays at Wheatstone to the late arrival of modules from Malaysia and a lack of engineering before the final investment decision.

The Ichthys offshore facilities from Korea were plagued with thousands of electrical fittings in hazardous areas that could have caused a fatal explosion.

One industry veteran described the final stages of recent LNG projects as "Aussies tasked with piecing the Lego together with parts broken or delivered late and half the instructions missing."

Boiling Cold understands there was a strong push within Shell for the Prelude to leave Korea before it was ready to tick a box on an internal corporate target.

While Australia saw little benefit from the construction of Prelude, it will have its carbon emissions as a liability on its books for decades.

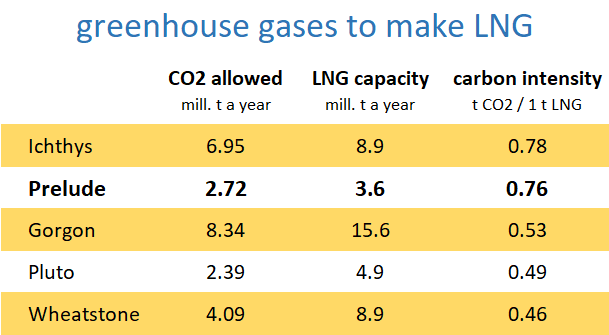

When Shell issued Prelude's environmental impact statement in 2009, it estimated annual greenhouse gas emissions would be equivalent to 2.29 million tonnes of carbon dioxide. A decade later Prelude is allowed to emit 2.72 million tonnes of CO2e a year under the safeguard mechanism administered by the Clean Energy Regulator.

This 20% increase in allowed emissions compared to what was promised in 2009 means LNG from Prelude is the second most carbon-intensive product from the recent offshore LNG boom in Australia.

When LNG projects start-up emissions are often high for a few months, but Prelude's initial performance has been appalling. In the 12 months to June 2019 Prelude emitted 2.3 million tonnes of greenhouse gases for just one cargo of LNG.

During the current shutdown gas flowing from the wells is more than Prelude requires to power itself and the excess gas is being flared, adding more carbon emissions with no resultant production.

Shell's environmental plan to flare only during "emergency situations, shutdowns and unplanned outages" did not contemplate shutdowns becoming commonplace rather than exceptional.

The oil and gas giant's total carbon emissions for 2019 were 70 million tonnes. Shell's share of Prelude's allowed emissions is 1.84 million tonnes a year. Floating LNG is adding little to Shell's production but an enormous amount to its carbon footprint.

Shell, like all investors in Australian LNG, has little incentive to reduce emissions as the Federal Government routinely lifts allowable emission limits if they are breached.

The Paris Agreement commits Australia to reduce its emissions by 26% to 28% from 2005 levels by 2030. Every extra tonne of CO2 Prelude emits will eventually have to be countered elsewhere in the economy by spending to reduce emissions, the purchase of offsets or reduced economic activity.

While the broader Australian economy will eventually shoulder the burden of Prelude's carbon emissions, Australia is likely to receive little company tax and no payments for the gas extracted.

CPC in Taiwan, for example, does not own its Australian subsidiary OPIC Australia directly but through a company registered in the well-known tax haven Panama. OPIC Australia owed related companies $US1.02 billion at December 2019, more than the total it has spent on Prelude.

The interest payments on this debt will reduce any company income tax paid should the Prelude ever turn a profit. Most foreign investors in Australian oil and gas use similar arrangements.

Shell will be able to use losses on Prelude to reduce the tax it pays on other Australian investments such as the North West Shelf, Gorgon and QGC LNG projects.

The nearby Ichthys project is forecast never to pay Australia for the gas it extracts according to the analyst Inpex hired to report on the project's economic impact, ACIL Allen executive director WA and NT Mr John Nicolaou.

Prelude is less likely than Ichthys to pay for its gas as the Petroleum Resource Rent Tax rewards delayed projects with annual escalations in credits for capital expenditure.

Prelude may operate reliably at full capacity in the future, but the returns to all the investors will be poor at best.

Shell, that wants to offload high-carbon projects from its portfolio, will find it difficult to sell out of Prelude. No other company would wish to take responsibility for the unique and complex technology.

Australia, after receiving little benefit from Prelude's construction and no gas domestic gas supply, is unlikely to receive financial returns from Prelude apart from operating expenditure with further costs inevitable somewhere in the economy to counter Prelude's carbon emissions.

A prelude is defined as an introduction to something important.

What Shell's Prelude should introduce is the understanding that Australia should not rely on bright shiny promises from proponents of resource projects.

OPIC Australia was asked for comment and did not respond. Shell declined to comment.

Correction 15 October 2020: units for "unit cost" in the "cost to build LNG capacity" were "$US/tonne", now corrected to "$US1000/tonne/year."

Main Picture: First LNG cargo left Prelude in June 2019. Source: Shell

All the info and a bit of comment on WA energy, industry and climate every Friday