Shell, Exxon and Chevron slammed on climate by court and investors: what it means for Australia

Shell, Exxon and Chevron are big players in Australian oil and gas and being forced to decarbonise sooner will affect their local operations, with a possible king hit to Prelude.

ANALYSIS

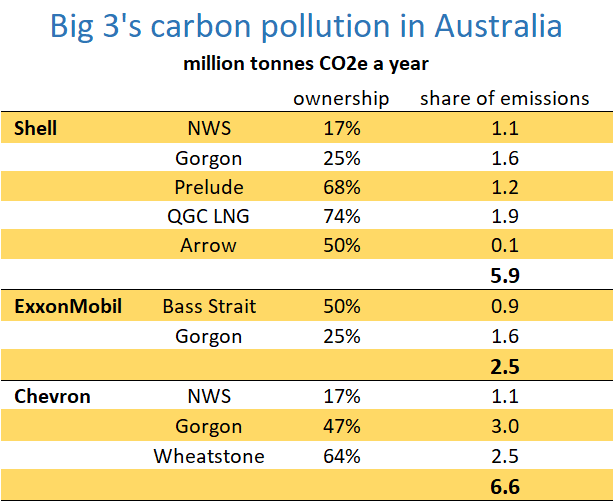

The three oil and gas supermajors with the biggest presence in Australia were yesterday all forced to hasten their moves away from fossil fuels.

Shell, ExxonMobil and Chevron have no plans to expand production in Australia, but the successful climate initiatives could affect operations, asset sales, and the closure of fields.

Dutch giant Shell was the first to fall when a court in its home country ruled it must cut its emissions by 45 per cent by 2030, including the Scope 3 emissions of its customers.

Shell had planned a 20 per cent cut in the carbon intensity, or carbon pollution per unit of energy delivered, of its products by 2030 with a further 15 per cent reduction five years later. However, a lower carbon intensity does not necessarily require a cut in total emissions, as it could be achieved with greater production of slightly less polluting products.

Shell wants its fossil fuels to be less dirty. The court wants less fossil fuels.

Shell will appeal the ruling.

Across the Atlantic, ExxonMobil next felt the heat when at least two activist investors were elected to the board of what was once the world’s largest company. The win at Exxon’s virtual AGM was a colossal rebuff to chair and chief executive Darren Woods, who had battled to keep the status quo of tame directors who support management standard in US oil companies.

The independent directors presented a plan for the US major to accept carbon capture and storage cannot save its business model and only fund new production that can deliver high returns with conservative oil price assumptions. The money freed up by forgoing lower return investments would be returned to investors or channelled to other growth opportunities.

Hours later, 61 per cent of Chevron shareholders voted for Chevron to “substantially reduce the greenhouse gas emissions of their energy products in the medium and long term.”

Chevron has no targets to reduce the Scope 3 emissions produced by customers burning its products and does not even target a reduction of its own Scope 1 emissions. Australia’s largest foreign investor does aim for a 40 per cent cut from 2016 to 2028 in carbon emissions for each barrel of oil produced, and a 25 per cent reduction for gas.

The wording of the resolution gives Chevron management plenty of wriggle room if they choose to keep their current course, but the strength of the vote indicates that it could be a career-limiting move come the 2022 AGM.

The rebuffs to the three multinational’s plans to navigate the energy transition are all different, but the effect will be similar: a stronger push to cut production, starting with the dirtiest and lowest return assets.

Local producers Woodside and Santos will note yesterday’s events. They bucked the global trend and escaped any successful climate-related votes at recent annual general meetings, but their management may not be so lucky in 2022.

Shell and Exxon will be keen for Chevron to finally get CO2 injection at the Gorgon LNG project working reliably to reduce the project’s carbon emissions by four million tonnes a year. Injection is now limited to one-third of design capacity until Chevron convinces the regulator it has fixed technical problems that could cause excessive pressure in the underground reservoir.

With CO2 injection working, Gorgon produces LNG with a relatively low carbon intensity and would not be a high priority for disposal.

Chevron would welcome a buyer of its North West Shelf LNG interest to immediately reduce emissions and escape looming significant decommissioning liabilities. However, with the Browse fields unlikely to ever be developed to fill the NWS plant and the Australian Government making strong moves to ensure decommissioning is done not delayed, the stake is a less than compelling buy.

Shell may be similarly keen to dispose of its NWS stake. However, it has the added complication that an exit would be an admission that it sees its 27 per cent stake in Browse as a stranded asset.

Shell’s problem child, Prelude floating LNG, is an asset particularly unsuited to the carbon transition: expensive, for two years now incredibly unreliable, and even if Shell gets excessive flaring under control its LNG is highly carbon-intensive.

The vessel is almost unsellable due to its unique complexity and poor performance.

A decade ago an oil and gas major would do anything to avoid the embarrassment of decommissioning a $US17 billion showpiece asset a few years after startup.

In today’s world, it just might be the symbolic move Shell needs to show investors it is serious about discarding its fossil fuel past.

Main image: Shell's Prelude floating LNG vessel flaring gas. Source: Anon.