WA environmental watchdog backs Kimberley fracking

The green light for Black Mountain Energy comes just months after Federal experts said its environmental risk assessment was "limited and disjointed" and reached "largely unsupported" conclusions.

The $2.3 billion-plus decommissioning on a WA nature reserve will be part-funded by the Federal and WA governments returning about half the royalties they received over six decades.

In May, Chevron stopped producing oil on Barrow Island off the WA coast, and the clock on a 40-year-old agreement started ticking which will likely require the Federal and WA governments to pay more than $500 million towards the clean-up bill.

After drilling about 900 wells over six decades, it will cost Chevron more than $2.3 billion to clean up the offshore nature reserve, according to a WA government minute obtained by a Boiling Cold freedom of information request.

During that time, Chevron produced 335 million barrels of oil and paid more than $1 billion in royalties, or about $3 per barrel.

In the coming years, about half of those royalties will flow back to Chevron and its partners to offset their clean-up costs, diminishing the total value Australia got from the extraction of its resources.

Since 1985, royalties paid for extracting oil from under Barrow Island have been calculated under a WA Act written especially for the project.

The royalty - 40 per cent of the difference between Chevron's sales revenue and operational costs - has been paid 75 per cent to the Federal Government and 25 per cent to WA.

However, under the Act, from May 2025, when production ended, and for the following three years, the calculation operates in reverse.

Chevron and its partners will be refunded 40 per cent of what they spend on decommissioning the oil field infrastructure before 31 December 2028, with the two governments paying in the same ratio they received royalties. The total refund is capped at the value of all royalties received.

In the absence of any information from Chevron, in 2022, the WA mining regulator used a media report that $1.29 billion of a total bill $2.3 billion would be spent in the royalty refund period to calculate that the state would refund about $129 million in royalties.

This implies the Federal Government would pay $387 million, with Chevron and its partners receiving a total of $516 million.

However, the refund could be higher, as the cost is now estimated to be more than $2.3 billion. Additionally, there is a considerable incentive for Chevron to do as much work as possible before 2029 to maximise the refund.

In May, the same month production ended, Chevron informed its regulator, the Department of Mining, Petroleum and Exploration (DMPE), that an unknown amount of gas was seeping to the surface near its old oil wells. The seeps add to widespread contamination of Barrow Island by Chevron.

A Chevron spokesman said while some costs would be refunded, it and its partners, Santos and ExxonMobil, would bear the vast majority of the total cost.

"We will continue to engage with state and federal governments in relation to the WA Oil decommissioning project and the administration of the royalty regime,” he said.

Neither government seems to know what it might have to pay to Chevron.

A DMPE spokesman said the cost was not included in its forward estimates, but the potential liability was "recognised as a non-quantifiable contingent liability" in the Annual Report on State Finances.

The report acknowledged that "a significant amount of royalties will need to be refunded," but only after Chevron pays the costs and the state verifies and audits them.

It is understood that the Federal Government is waiting on WA to determine the total refund, as the state administers the royalty regime.

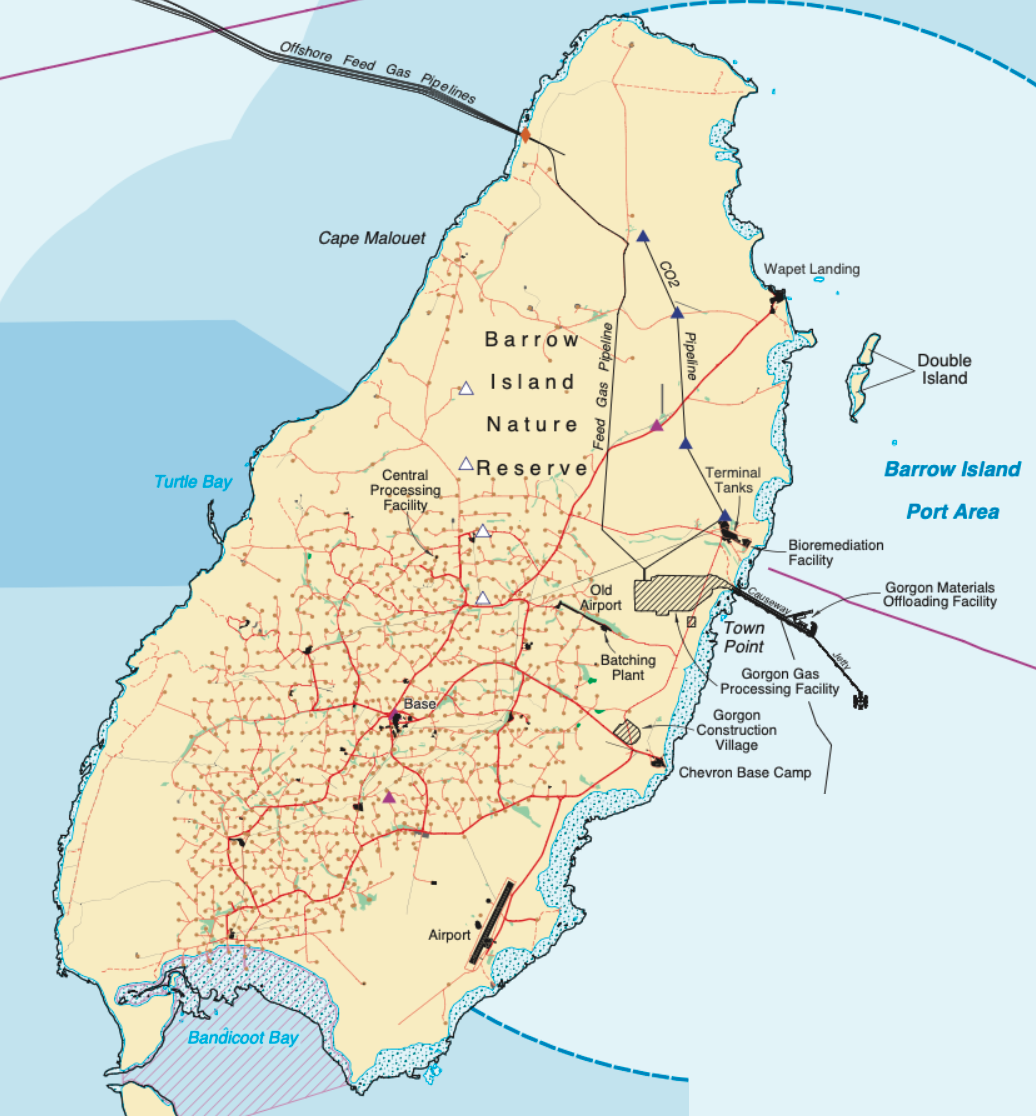

The scope of the clean-up is enormous and complicated.

About 700 of the almost wells 900 are more than 40 years old, according to the WA Government's database of wells.

At the start of 2025, 316 wells were still producing about 3600 barrels of oil a day, according to an environment plan lodged by Chevron.

Up to four drilling rigs will plug and abandon the wells—a procedure that permanently seals the oil and gas underground, typically using cement. Two rigs may operate 24 hours a day.

Then, the wellheads are removed, as well as almost all other equipment and their concrete foundations. Sixteen areas contaminated with hydrocarbons require attention.

All this must be done on a hot, exposed island 70km of the north-west coast of WA while not causing further contamination, managing fire risk and protecting the vast array of native species that flourish on the island due to a lack of introduced weeds and predators so common on the mainland.

Afterwards, the giant Gorgon gas export plant, also operated by Chevron, will remain on the island.

The shuttered oil asset on Barrow Island is owned by Chevron (57 per cent), Santos (29 per cent), and ExxonMobil (14 per cent).

If cleaning up Barrow Island does cost $2.3 billion, Santos will have to contribute $667 million.

The work has begun as the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company conducts due diligence on Santos in preparation for a potential takeover.

Whether the $6 billion decommissioning liability Santos reports on its balance sheet is adequate to cover the work it must do across its operations is reportedly a focus of due diligence underway to support the $36 billion takeover.

In WA, Santos will soon start decommissioning the Ningaloo Vision oil production vessel and has substantial ongoing work around the Varanus Island gas hub.

The Adelaide-based company plans to use its shuttered Reindeer and Bayu Undan gas platforms in WA and Timor-Leste waters to store CO2 under the seabed. If these projects do not eventuate, it may have to decommission them decades earlier than planned.

The other equity holder in Barrow Island - ExxonMobil - is under instructions from the offshore regulator NOPSEMA to plug 180 wells and dismantle ten platforms in the Bass Strait. The cost - likely to be in the billions of dollars - will be shared with its 50 per cent partner Woodside.

ExxonMobil, like Santos, had hoped to delay some of the expense by using a platform for carbon storage but withdrew an application for environmental approval in March.

The total bill to 2050 to clean up after Australia's offshore oil and gas industry was estimated to be $52 billion four years ago, with onshore operations, such as those on Barrow Island, incurring additional costs.

However, decommissioning is inherently unpredictable as it involves old equipment with uncertain levels of contamination and structural integrity, and costs are often more than expected.

Decommissioning just one oil field - the Northern Endeavour vessel and its wells and pipelines on the seabed - is expected to cost $1 billion.

Woodside surprised investors earlier this year when it announced it could spend up to $1.6 billion on decommissioning this year, well above the expectations of analysts.

All the info and a bit of comment on WA energy, industry and climate every Friday