🗡️ Who murdered the Murujuga rock art science?

Special Cluedo™️ edition 🔍 Was it Mr Cook or Prof Smith?

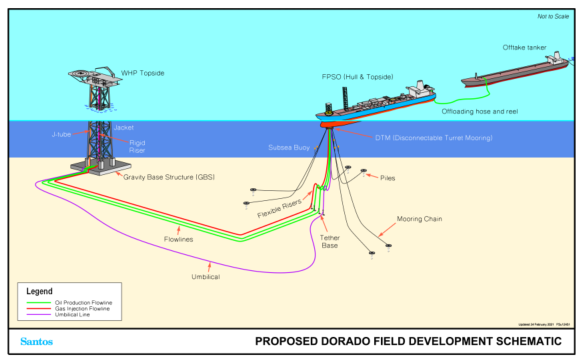

Santos wants to approve its $2.8B Dorado oil project off WA in mid-2022 but science and the law will provide hurdles to its 165 million tonnes of carbon pollution.

Santos' Dorado oil project off WA would result in 165 million tonnes of carbon emissions, equivalent to 46 years of operation of Collie's Muja power station, according to an environmental approval submission released today.

The $US2 billion ($2.8 billion) Dorado project off WA could produce up to 350 million barrels of oil over 20 years from 2025.

Direct, or Scope 1, greenhouse gas emissions from operating the wellhead platform and floating oil vessel are estimated to be the equivalent of 15 million tonnes of CO2 during the life of the project, according to the Offshore Project Proposal submitted by Santos to the National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority.

Carbon pollution from customers burning the oil, known as Scope 3 emissions, would create another 150 million tonnes of CO2e.

In comparison, Synergy's ageing Muja power station in Collie emitted 3.6 million tonnes of CO2e in the 12 months to June 2020.

The Dorado oil field was discovered by Quadrant Energy in mid-2018 in the then relatively under-explored Bedout Basin north of Port Hedland. Santos bought Quadrant some months later.

Santos chief executive Kevin Gallagher told investors on Tuesday that the oil-only Dorado Phase 1 was on track for a final investment decision in mid-2022.

"The second phase of gas development to backfill a domestic gas infrastructure and WA is likely to occur in the second half of the decade," Gallagher said.

"Dorado is a very low CO2 reservoir with approximately 1.5 per cent CO2 and with all gas reinjected in the initial phase,

"This makes it one of the lowest emissions-intensive oil projects in the region."

Whether Dorado Phase 1's emissions are considered low or high will be a major influence on its environmental approval process.

Conservation Council of WA director Piers Verstegen said proposals like Dorado were alarming.

"This is exactly the kind of development that the International Energy Agency and the world’s climate scientists have said cannot proceed if we are to maintain a habitable planet," Verstegen said.

"I expect environment groups will be applying significant scrutiny on the proposal."

NOPSEMA grants environmental approval for offshore oil and gas projects, whereas almost all other activities are assessed under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act and decided by the Federal Environment Minister.

The three approvals for large oil and gas projects granted to date under NOPSEMA's Offshore Projects Proposal process have all taken more than a year from submission to acceptance.

For Santos to sanction Dorado in mid-2022 it will have to navigate the approval process quicker than Barossa, Scarborough and Crux despite signs that the legal and scientific opportunities for approval have recently narrowed substantially.

Barossa, Scarborough and Crux all supply gas to LNG plants. LNG producers argue that their significant Scope 1 emissions in Australia and Scope 3 emissions from customers burning the gas are a net climate benefit as the product displaces even dirtier coal.

While this argument is not universally accepted, it certainly does not apply to an oil project.

Two oil developments by micro oil and gas company Kato Energy approved in April are a fraction of the size of Dorado and only produce for a handful of years.

With a large long-life oil project, Santos is treading a new path through NOPSEMA's approvals process and wants to do it in record time.

Part of Kato's argument for the acceptance of its Amulet and Corawa developments off WA was that the IEA's sustainable development scenario in its 2020 World Energy Outlook "recognises that there remains a role for oil...for the foreseeable future."

NOPSEMA sought the advice of the Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources that supported Kato's proposals as "new oil fields will be required at least until 2040 and this is supported by the WEO 2020 SDS."

A month after NOPSEMA signed off Kato's projects on April 19 the wheels fell off this argument.

In May the IEA released its pathway to net-zero emissions by 2050 that concluded that success required no new oil or gas projects.

The next week the Federal Court handed down the historic Sharma decision concerning the approval of a coal mine in NSW by the Federal Environment Minister Sussan Ley.

Justice Bromberg found that it was mandatory for the Minister to consider potential harm to children.

In particular, Bromberg noted, "a reasonable Minister for the Environment ought to have the children in contemplation when facilitating the emission of 100 million tonnes of CO2 into the earth’s atmosphere.”

Dorado's emissions are 65 per cent higher than the coal mine.

Lawyers from Allens noted in a summary of the decision that "those in charge of approving carbon-intensive projects may now be more alive to climate change-related issues and place greater weight on those risks when making decisions."

"Those in charge" includes NOPSEMA, which is an independent authority and will be well are of the Sharma decision and the potential for successful litigation on similar grounds.

Ley has appealed the decision.

The Federal Court's finding that it was reasonably foreseeable that the coal project's Scope 3 emissions would risk harm to Australian children has been bolstered by the release of the IPCC update on climate science earlier this month.

Dorado's approval could get even more difficult in late October at the UN Climate Change Conference in Glasgow when countries are excepted to strengthen their targeted emissions cuts, leaving even less room for Dorado's 165 million tonnes.

Australasian Centre for Corporate Responsibility director of climate and environment Dan Gocher said Santos' pursuit of the Barossa, Dorado and Narrabri projects confirmed its climate commitments were nothing but greenwashing.

"Santos intends to rely almost exclusively on unproven carbon capture and storage at Moomba to deliver its 2040 net-zero target," Gocher said.

"And Santos has refused to set targets for its Scope 3 emissions, which are by far the largest proportion of its carbon footprint,

"The current consolidation in the oil and gas industry is likely to have terrible climate consequences.

"Santos' proposed merger with Oil Search will provide it with the further capital to develop multiple new projects, in defiance of the IPCC's recent 'code red' warning."

Boiling Cold has asked Santos how Dorado is compatible with net-zero emissions by 2050 and if it expects legal actions that could delay approval.

ASX-listed junior Carnarvon Petroleum owns between 20 and 30 per cent of the Santos-operated permits under and around Dorado.

Main image: Graphic of the floating production storage and offloading (FPSO) vessel proposed for Santos's Dorado oil project off WA. Source: Santos presentation.

All the info and a bit of comment on WA energy and climate every Friday