WA government investigating if one dead tree could halt Alcoa's mining

If the US miner is found to have mined too close to a large jarrah tree, it would trigger an automatic cancellation of its right to mine much of its lease.

Several big green hydrogen projects have been shelved. An expert explains why Australia’s sky-high ambition for the industry is struggling to reach fruition.

Alison Reeve, Grattan Institute

As the world looks for ways to tackle climate change, Australia has invested heavily in green hydrogen.

Green hydrogen is shaping as the best option to strip carbon emissions from some industrial processes, such as iron-making and ammonia production. But making the dream a reality in Australia is proving difficult.

Two recent announcements are a case in point. This month, the Queensland government withdrew financial support for the Central Queensland Hydrogen Hub. It came weeks after energy company Fortescue cut 90 green hydrogen jobs in Queensland and Western Australia.

I led the development of Australia’s National Hydrogen Strategy in 2019, in my previous job as a federal public servant. I also co-authored a Grattan Institute report on how hydrogen could help decarbonise the Australian economy. Here, I explain the main challenges to getting the industry off the ground.

Hydrogen is the lightest and most abundant element in the universe. It’s usually found as a gas, or bonded to other elements.

It’s used to make products such as fertilisers, explosives and plastics. In future, it may also be a zero-emissions replacement for fossil fuels in industries such as steel and chemicals manufacturing.

Australia currently makes very low volumes of hydrogen using natural gas, which produces greenhouse gas emissions. We are well-placed to produce “green” or zero-emissions hydrogen, through a process powered by renewable energy which releases hydrogen from water.

But creating a large green hydrogen industry won’t be easy. These are the main five challenges.

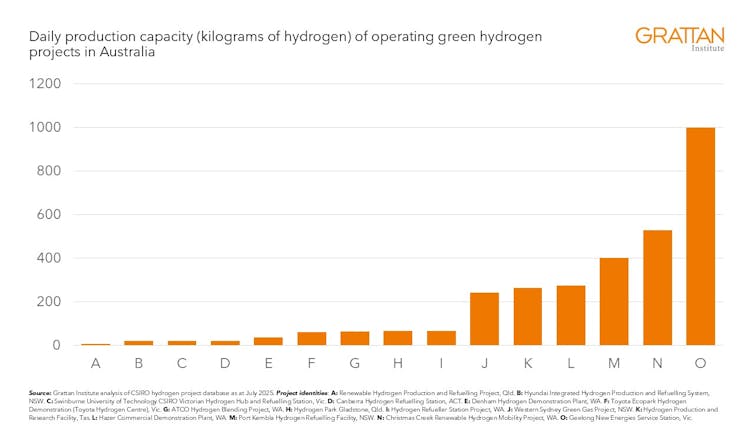

About 15 facilities in Australia are currently producing green hydrogen, all at low volumes – between 8 kilograms and one tonne a day (see chart below).

By contrast, most recently cancelled projects would have produced hundreds of tonnes of green hydrogen daily. The Central Queensland Hydrogen Hub, for example, would initially have produced about 200 tonnes a day, scaling up to 800 tonnes in the 2030s.

The failure of these big projects shows Australia has much to learn about planning, building, commissioning and operating large green hydrogen facilities.

Very little hydrogen is currently used in Australia – around 500,000 tonnes a year. This is less than 1% of national energy consumption.

Most of this hydrogen is produced using natural gas, and is produced on site at existing industrial operations that require hydrogen, such as oil refiners and ammonia plants. Using hydrogen from a different source would require major – and costly – engineering changes at these facilities.

So, how do new green hydrogen producers create demand for their product?

The first option is to convince a company to spend money changing their operations to bring in green hydrogen from outside. This is not an easy prospect. The second is to find big new markets – which leads to the next challenge.

Renewable hydrogen isn’t a direct substitute for conventional fuels.

You can’t burn hydrogen in your gas stovetop without changing the pipes in the house and the burners on the stove. Likewise, you can’t use hydrogen as a substitute for coal when making steelwithout changing the smelting process.

This creates a chicken-and-egg problem. Green hydrogen proponents won’t invest in high-volume production unless there are large users to buy the product. But large users won’t invest in changing their processes unless they are assured of supply.

Green hydrogen is much more expensive than conventional hydrogen. And as yet, there’s little evidence buyers are willing pay more for it.

So for green hydrogen to compete with conventional production, it needs government subsidies.

The huge expense is largely due to the electricity used to make green hydrogen – prices of which are currently high.

As renewable energy expands, electricity prices in Australia are expected to fall. But building more large-scale renewable generation in Australia is itself a difficult prospect.

Recent turmoil in global markets has made companies more cautious about investing outside their core business. And global inflation has helped drive up the cost of electricity needed to produce green hydrogen.

Globally, governments have scrambled to keep national economies afloat, which has led to cuts in green hydrogen in several countries.

In Australia, green hydrogen is still key to the Albanese government’s Future Made in Australia policy. And hydrogen has been a rare area of agreement between the two major parties, at both federal and state levels.

But there are signs this is changing. The federal opposition last year fought the government’s hydrogen tax credits, and the withdrawal of support for the Central Queensland Hydrogen Hub came from the Queensland LNP government, which won office in October last year.

There is a long road ahead if green hydrogen is to help Australia reach its goal of net-zero emissions by 2050.

So what have we learned so far?

Many scrapped projects tried to implement a “hub” model – combining multiple users in one place, which was designed to make it more attractive to suppliers. But this was difficult to co-ordinate, and vulnerable to changing global conditions.

The green hydrogen industry should focus on the most promising uses for its product. For example, if it could successfully make enough green hydrogen to supply ammonia production, it could build on this to eventually support a bigger industry, such as iron-making.

It’s also time to rethink how subsidies are structured, to reflect the fact some sectors are better bets than others. At present, the federal government’s Hydrogen Headstart program and the hydrogen tax credit are agnostic as to how the hydrogen is used, which does little to help demand emerge in the right places.

Finally, political unity must be renewed. Hydrogen projects require a lot of capital, and investors get nervous when an industry does not have bipartisan support.

The hype around green hydrogen in Australia is fading. There are some reasons for hope – but success will require a lot of hard work.

Alison Reeve, Program Director, Energy and Climate Change, Grattan Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

All the info and a bit of comment on WA energy, industry and climate every Friday